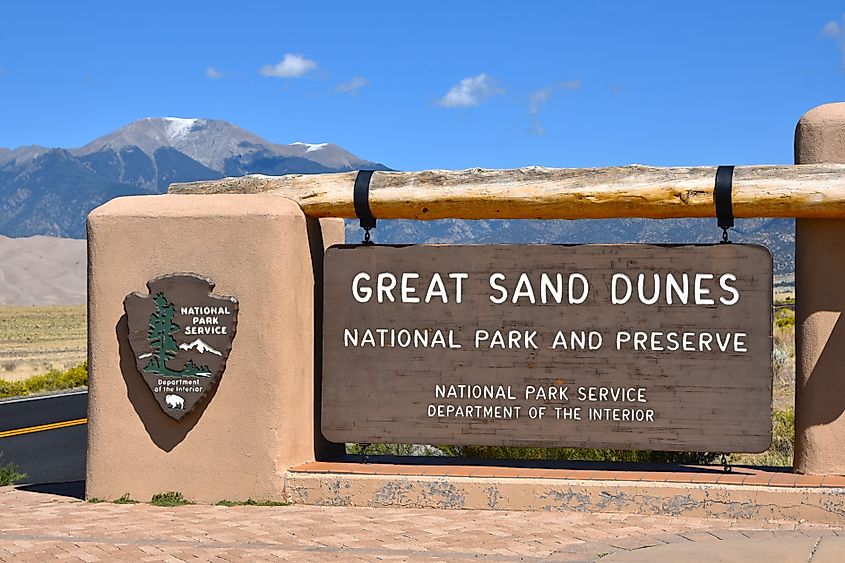

Great Sand Dunes

Tucked against the jagged spine of Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve is home to the tallest sand dunes in North America. Rising more than 750 feet from the San Luis Valley floor, these towering ridges of golden sand look like a mirage against the alpine peaks behind them. But this surreal terrain is very real—shaped by thousands of years of wind, water, and geologic forces—and it’s one of the most ecologically diverse and visually arresting places in the American West.

Where the Desert Meets the Mountains

Located in south-central Colorado, about 25 miles northeast of the town of Alamosa, the park spans more than 150,000 acres of sand, wetlands, grasslands, and mountain wilderness. Its elevation range is dramatic: from the base of the dunes at about 7,500 feet to alpine summits reaching over 13,000 feet. At the heart of the park are the dunes themselves—an iconic, rippling sea of sand that sprawls for miles and seems entirely out of place in the snow-fed landscape of the southern Rockies.

What makes this setting truly unique is not just the scale of the dunes but the ecological and geological contrasts all around them. You can climb a sand peak in the morning, cool off in a snowmelt-fed stream by midday, and hike through aspen and spruce forests to alpine lakes by afternoon—all without leaving the park boundary.

How Did These Sand Dunes Form?

The formation of the dunes is a product of two powerful forces: wind and water. For thousands of years, prevailing southwesterly winds funneled through the San Luis Valley, picking up sand and volcanic particles from the valley floor—much of it deposited by ancient lakes and streams fed by the surrounding San Juan and Sangre de Cristo mountains.

As the wind surged across the flat basin, it slammed into the base of the Sangre de Cristo Range, abruptly losing energy and dropping its sandy cargo. Over time, these deposits grew into an expansive dune field, with the tallest dunes forming where wind patterns became especially complex.

One of the most fascinating features of the park is Star Dune—the tallest in the park and the country—reaching an impressive height of over 750 feet. Unlike simpler barchan or transverse dunes, Star Dune was shaped by shifting wind patterns from multiple directions. This prevents sand from blowing off in any one direction and instead causes it to build up vertically, forming a massive, multi-armed structure that defies the simplicity of typical desert formations.

The Science of Shifting Sand

Sand dunes might look static, but they are anything but. The dunes are in constant motion, shaped and reshaped by the wind. The angle at which sand piles up before collapsing under its own weight is known as the "angle of repose"—typically around 30 to 34 degrees. As sand accumulates and topples, the dunes actually migrate over time, moving in the direction of the prevailing winds.

Great Sand Dunes National Park contains a variety of dune types:

-

Star Dunes: Formed by multidirectional winds and known for their great height and complex shapes.

-

Barchan Dunes: Crescent-shaped dunes that move in the direction of the wind. These are rare in the park.

-

Transverse Dunes: Long ridges formed perpendicular to wind direction.

-

Parabolic Dunes: U-shaped dunes anchored by vegetation, with the open side facing upwind.

-

Nebkha Dunes: Small mounds of sand collected around vegetation, essentially the early stage of parabolic dunes.

Each dune type tells a story about the wind, vegetation, and geography of the region.

More Than Just Sand: Diverse Ecosystems

While the dunes get all the attention, the park’s ecosystems are equally compelling. The vast elevation range—from high desert to tundra—creates a rare diversity of habitats. The base of the dunes supports hardy grasses and shrubs. The adjacent mountain slopes are home to cottonwood, pine, and aspen forests, giving way to spruce and fir at higher elevations. In summer, wildflower-filled alpine meadows bloom with color, providing habitat for marmots, pikas, and a wide range of bird species.

Small mammals like kangaroo rats thrive in the sands, and several species of endemic insects have adapted to life on the dunes. Higher up, black bears, elk, and bighorn sheep roam the preserve. Numerous alpine lakes and wetlands—some of which feed into the famed Medano Creek—dot the park, providing critical water sources for wildlife and humans.

Medano Creek: A Beach in the Mountains

One of the most surprising features of the park is Medano Creek, a seasonal stream that flows at the base of the dunes. Fed by snowmelt from the Sangre de Cristos, the creek typically peaks in late spring and early summer. During this time, it becomes a popular spot for visitors to wade, splash, and even skimboard—a mountain beach like no other.

What makes Medano Creek even more unusual is its “surge flow”—waves that appear to pulse down the streambed. This phenomenon happens when sand temporarily dams the shallow creek, then bursts forward, creating rhythmic waves every few seconds.

A Landscape Shaped by Weathering and Erosion

While the dunes are a symbol of stability, they owe their existence to processes of constant change. Weathering—the breakdown of rocks and minerals by wind, water, and temperature changes—generates the raw material for the dunes. Erosion, meanwhile, transports these particles from the surrounding mountains and valley floors into the main dune field.

The park acts as a natural sediment recycling system. Streams and wind carry sand away from the dunes and into nearby grasslands or wet meadows, where it can settle and eventually be picked up again and returned to the dune field.

Most of the sand in the park is alluvium—sediment carried by water. During ancient times, when the San Luis Valley held a large lake, wave action and stream outflows deposited layer after layer of fine particles. As the climate dried and the lake receded, winds took over, sculpting the landscape we see today.

A Human History That Spans Millennia

The Great Sand Dunes are not just a natural wonder; they’re also a place of deep human history. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of human presence dating back over 11,000 years, including tools from the Clovis culture, one of the earliest known groups in North America.

In more recent centuries, the Ute people, who still have ancestral ties to the region, hunted and lived in the mountains and valleys surrounding the dunes. Spanish settlers arrived in the 1600s, followed by Anglo-American homesteaders and ranchers in the 19th century.

The dunes were designated a national monument in 1932, but it wasn’t until 2004 that they became Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, thanks to federal legislation that expanded the park and added protections for the surrounding forest and watershed.

Visiting the Great Sand Dunes Today

Great Sand Dunes National Park is open year-round, but the experience changes dramatically by season. Late spring and early summer are ideal for seeing Medano Creek in full flow. Summer brings intense sun and high temperatures on the sand, which can reach over 150°F by midday. Fall offers cooler weather and stunning foliage in the mountains. Winter brings snow to the high peaks and a serene, quiet beauty to the dunes.

Popular activities include:

-

Sandboarding and sand sledding: Rentals are available locally.

-

Hiking Star Dune: A challenging 6-hour round trip with no marked trail.

-

Backpacking in the preserve: Trails lead to alpine lakes, waterfalls, and panoramic ridgelines.

-

Wildlife viewing: Best at dawn and dusk.

-

Stargazing: The park is an International Dark Sky Park, offering some of the best night skies in the US.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the tallest sand dune in North America?

Star Dune in Great Sand Dunes National Park, which rises over 750 feet.

When is the best time to visit Medano Creek?

Late May through early June, when snowmelt is at its peak.

Can you hike to the top of the dunes?

Yes. There are no marked trails, but visitors can freely climb the dunes—Star Dune takes about 6 hours round trip.

Is the park good for stargazing?

Yes. It's an International Dark Sky Park with excellent conditions for night photography and stargazing.