7 Historical Places in New Mexico You Can Still Visit

New Mexico carries its history on the surface. Ancient roads cut through open desert. Adobe walls still hold the day’s heat after sunset. Centuries of cultural exchange left marks that are still visible and open to the public. This is not history locked behind glass. It is history that can be walked, climbed, photographed, and felt underfoot.

Long before statehood, this land supported thriving Indigenous civilizations, Spanish colonial settlements, military outposts, and frontier towns shaped by trade and conflict. Many of those places survived because the landscape protected them. Others endured because communities refused to let them disappear. Today, these sites offer rare continuity, linking modern travelers with stories that stretch back hundreds or even thousands of years.

Here are seven historical places in New Mexico that remain open, preserved, and deeply connected to the state’s identity.

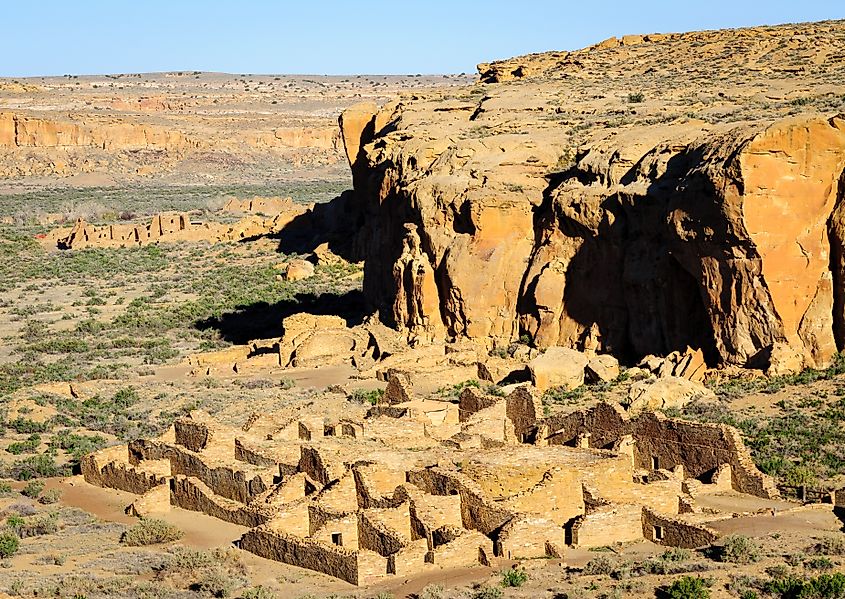

Chaco Culture National Historical Park

Chaco Canyon stands as one of the most important archaeological sites in North America. Located in the high desert of northwestern New Mexico, this UNESCO World Heritage Site preserves the remains of a complex Ancestral Puebloan society that thrived between AD 850 and 1250.

Massive stone houses dominate the canyon floor. Pueblo Bonito alone once contained more than 600 rooms arranged in precise geometric patterns. Roads radiated outward for miles, connecting distant communities to the canyon’s ceremonial core. Builders aligned structures with solstices and lunar cycles, revealing advanced astronomical knowledge.

The scale of the masonry and the isolation of the setting suggest a place designed for gathering, ceremony, and governance rather than daily farming life. Petroglyphs etched into stone walls add another layer of storytelling.

Access requires planning. The park sits far from major highways, and dirt roads lead to the entrance. That remoteness has helped preserve the site and adds to its power.

Taos Pueblo

Taos Pueblo is among the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States. It holds UNESCO World Heritage status and National Historic Landmark recognition. Visitors may enter only during designated hours, with guidelines that respect residents’ privacy and religious practices. Photography restrictions apply during ceremonial periods.

The multi-story adobe buildings, rising from the Taos Valley north of Santa Fe, have stood for more than 1,000 years. Red clay walls, supported by wooden beams called vigas, form a living village rather than a static monument. Families still reside within the pueblo, maintaining traditions passed down through generations.

The Rio Pueblo de Taos flows nearby, providing water that sustained the settlement for centuries. This is not a reconstruction or a preserved ruin. It is a functioning community that adapts while honoring deep cultural roots.

Bandelier National Monument

Bandelier National Monument protects thousands of archaeological sites carved into the volcanic cliffs of the Pajarito Plateau near Los Alamos. The area preserves the homes and dwellings of Ancestral Pueblo people who lived here between AD 1150 and 1550.

Its soft volcanic tuff allowed residents to carve cave dwellings directly into canyon walls. Petroglyphs appear throughout the monument, etched into dark basalt rock. Many depict animals, symbols, and figures whose meanings are still debated by scholars.

Wooden ladders throughout give access to some alcoves. Stone masonry villages sit along the canyon floor, connected by footpaths and stairways. Paved trails and interpretive signs guide visitors through Frijoles Canyon, and backcountry routes lead deeper into quieter sections.

El Morro National Monument

El Morro rises from the plains of western New Mexico as a towering sandstone landmark that guided movement across the region for centuries. Long before modern roads, its silhouette signaled a dependable resource at its base. A natural water pool collected rain and snowmelt, offering a rare and reliable supply in an otherwise arid landscape. That water transformed the bluff into a strategic stopping point for Indigenous communities, Spanish expeditions, and later American travelers moving west.

The rock face became a record of that passage. Between the late 1500s and the 1800s, explorers, soldiers, settlers, and emigrants carved names, dates, and brief messages into the stone. One of the earliest inscriptions belongs to Juan de Oñate, dated 1605. Later carvings reflect military patrols and the steady push of westward expansion. Together, the inscriptions document centuries of movement through the region in a way few sites can match.

Above the pool, the mesa top holds the ruins of Atsinna, a Puebloan village established in the 1300s. Stone foundations still outline living spaces and communal areas that once supported hundreds of residents. The village location offered security, broad views of the surrounding plains, and direct access to the water below.

Palace of the Governors

The Palace of the Governors is the centerpiece of Santa Fe’s historic Plaza and holds the title of the oldest continuously occupied public building in the United States. Constructed in 1610, it served as the seat of Spanish colonial government, later transitioning through Mexican and American rule.

Thick adobe walls stretch along the north side of the Plaza, topped by a shaded portal where Native artisans sell handmade jewelry and crafts today. Inside, museum galleries trace New Mexico’s political, cultural, and artistic history.

Artifacts range from Spanish colonial furniture and religious art to maps, documents, and contemporary works. The building itself tells a story of adaptation, having been rebuilt and modified after revolts, occupations, and changing governments.

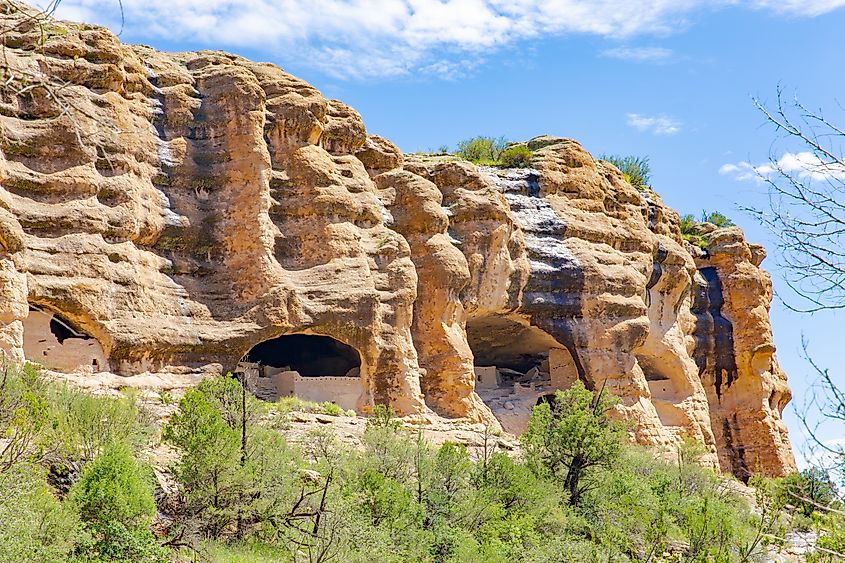

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument

The Gila Cliff Dwellings preserve the remains of a Mogollon community that lived in these caves during the late 1200s. Deep within the Gila Wilderness of southwestern New Mexico. The setting is strikingly remote, a factor that helped protect the site long after its original residents moved on.

These dwellings stand apart from many cliff sites across the Southwest. The Mogollon people constructed stone masonry rooms inside natural caves formed by erosion, using the rock overhangs as ready made shelter. Thick cave walls moderated heat and cold, and elevated entrances provided clear views across surrounding canyons and valleys. The location balanced protection, visibility, and access to nearby resources.

Access to the site comes via a short but steady hike through forested terrain. The trail leads directly into the caves, where intact rooms, doorways, and construction details are visible.

The surrounding landscape explains why settlement was possible here. Rivers and fertile lowlands supported hunting and farming, and nearby hot springs added another reliable water source.

Fort Sumner and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

Fort Sumner carries a complicated and painful history tied to the Bosque Redondo Reservation. Established in the 1860s, the fort became the site where thousands of Navajo and Mescalero Apache people were forcibly relocated during the Long Walk.

Harsh conditions, failed farming experiments, and inadequate supplies marked this chapter of American history. Many suffered and died before the Navajo were allowed to return to their homeland in 1868.

Today, the Bosque Redondo Memorial stands near the fort ruins, giving an honest and educational interpretation of the events that occurred here. Exhibits include personal accounts, artifacts, and contextual history presented in collaboration with descendant communities.

Fort Sumner also connects to frontier lore as the burial site of Billy the Kid, a young outlaw tied to New Mexico’s violent frontier era.

History That Still Lives on the Land

New Mexico’s historical places do not fade quietly into the past. They remain active, visible, and often deeply personal. These sites tell stories of innovation, endurance, conflict, and continuity shaped by the land itself.

Each location offers more than a lesson. It provides context for understanding how cultures adapted, resisted, and survived across centuries. Preservation allows those stories to remain accessible without flattening their complexity.

Walking these places brings history out of textbooks and into real space. That connection gives New Mexico a depth few states can match and allows its past to continue shaping the present.