The Chihuahuan Desert

The Chihuahuan Desert straddles two countries and is separated from nearby arid regions by two major mountain ranges: the Sierra Madre Occidental to the west and the Sierra Madre Oriental to the east. Approximately 9,000 years ago, this region was significantly wetter and its mountain slopes were covered by forests. As conditions grew drier over time, many species were isolated, evolved separately, or became extinct, leading to the distinct variety of plants and animals found in the Chihuahuan Desert today.

While deserts are often overlooked as havens for biodiversity, some of them support impressive numbers of species, including rare flora and fauna, specialized habitats, and unique ecological communities. In fact, the Chihuahuan Desert is regarded as the most biologically diverse desert in the Western Hemisphere and one of the most species-rich arid regions worldwide!

Unfortunately, it also faces severe threats. Issues such as overgrazing, depletion and diversion of water resources, changes in natural fire regimes, urban expansion, and overharvesting of native plants and animals pose significant risks to the survival of its ecosystems.

Geography and Climate

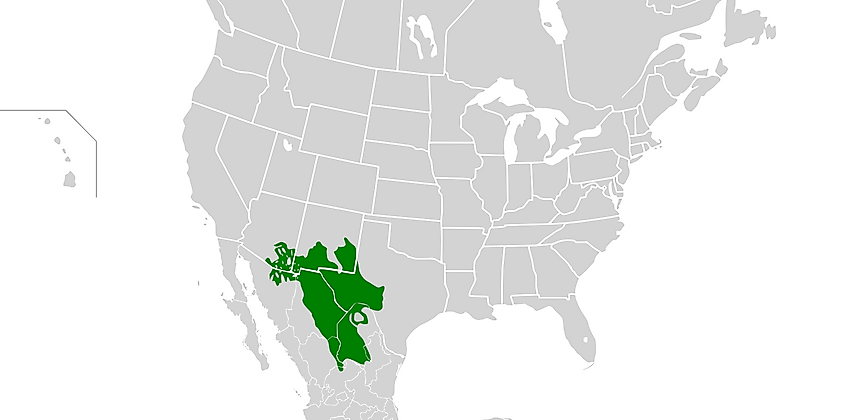

Encompassing around 250,000 square miles (647,500 square kilometers,) the Chihuahuan Desert Ecoregion is the largest desert in North America. More than 90% of its expanse lies within Mexico. It stretches for nearly 930 miles (1,500 kilometers,) from south of Albuquerque, New Mexico, to roughly 155 miles (250 kilometers) north of Mexico City. Within this region are parts of several Mexican states—Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, Zacatecas, Nuevo León, and San Luis Potosí—as well as the southeastern section of Arizona, large areas of New Mexico, and the Trans-Pecos area of Texas.

Unlike the Sonoran and Mojave deserts, the Chihuahuan Desert sees greater summer rainfall brought on by monsoon storms, along with cooler winter temperatures. Summers are hot, while winters tend to be cool to cold and generally dry. Annual precipitation ranges from about 6 to 20 inches (150 to 500 millimeters), with much of it arriving during the summer monsoon season. The landscape is defined by a basin-and-range structure, made up of broad desert valleys bordered by terraces, mesas, and mountain ranges. Because the region’s basins do not drain to the sea, rainwater often collects in salt lakes, or playas. Dune fields, formed by quartz or gypsum sand, are also common here.

Flora and Fauna

Along the eastern side of the Chihuahuan Desert lies one of the continent’s oldest and most botanically diverse areas. Numerous plant communities thrive within the ecoregion, transitioning from desert shrublands in lower elevations to conifer woodlands higher up. Overall, there may be as many as 3,500 different plant species, with nearly a quarter of the world’s cacti found here and around 1,000 species occurring nowhere else. Yucca woodlands, gypsum dunes, playas, and various freshwater habitats are notable ecosystem types within the desert. Extensive grasslands and a broad spectrum of yucca and agave species—many of which are endemic—underscore the desert’s ecological uniqueness.

More than 170 species of amphibians and reptiles inhabit the Chihuahuan Desert, including at least 18 that are found exclusively in this region. It also harbors a significant number of endemic fish: nearly half of the desert’s 110 fish species are confined to, or occur primarily in, isolated springs within closed basins.

The Chihuahuan Desert supports over 130 mammal species, among them mule deer, pronghorn, jaguar, javelina, and gray fox. Notably, it contains the continent’s largest remaining black-tailed prairie dog colony and is the only place where the endemic Mexican prairie dog still lives. Historically, this region was one of the few areas where grizzly bears, wolves, and jaguars roamed together. Today, large predators like mountain lions, jaguars, and golden eagles can still be found in certain locales.

Around 400 bird species can be spotted here, primarily widespread varieties with relatively few that are endemic. The desert’s grasslands are vital winter habitats for many Great Plains birds, including mountain plovers, ferruginous hawks, and Baird’s sparrows—species experiencing notable population declines. Additionally, neotropical migratory birds depend on riparian corridors along the Pecos and Rio Grande rivers for part of their migration journey.