The San Andreas Fault

Beneath the sunbaked highways, vineyards, and sprawling cities of California lies a geological behemoth—one capable of reshaping the landscape in an instant. The San Andreas Fault isn’t just a line on a map; it’s a colossal fracture in the Earth’s crust that has been quietly grinding for millions of years, storing unimaginable energy. While it may seem dormant on most days, this fault line has a dramatic history of unleashing powerful earthquakes that have left lasting scars on both land and memory—from the devastating 1906 San Francisco quake to the shaking of the 1994 Northridge disaster.

Yet, millions live and commute atop it, with roads, homes, and even a subway tunnel piercing through this restless boundary between tectonic giants. What exactly is the San Andreas Fault, and why does it matter so much to the people of California—and the world?

What Is the San Andreas Fault?

The San Andreas Fault is a transform fault, more specifically a strike-slip fault, which means that the two sides of the fault are sliding past each other horizontally. This fault forms a major boundary between two enormous sections of the Earth’s crust—the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate.

The Pacific Plate, to the west and south of the fault, is slowly grinding northward. Meanwhile, the North American Plate lies to the east and is shifting in a slightly different direction. The result? A constant buildup of stress that is occasionally released in the form of earthquakes—some minor, others catastrophic.

A Geologic Tug of War: Plate Tectonics at Work

According to plate tectonic theory, the Earth’s crust is broken into rigid plates that float on a softer mantle below. The San Andreas Fault represents the dynamic, friction-heavy edge where two of these plates meet. Over geologic time, the Pacific Plate has moved past the North American Plate at a rate of about 1 centimeter per year. However, more recent measurements suggest that the rate of movement has sped up, currently ranging between 4 and 6 centimeters (1.6 to 2.4 inches) per year.

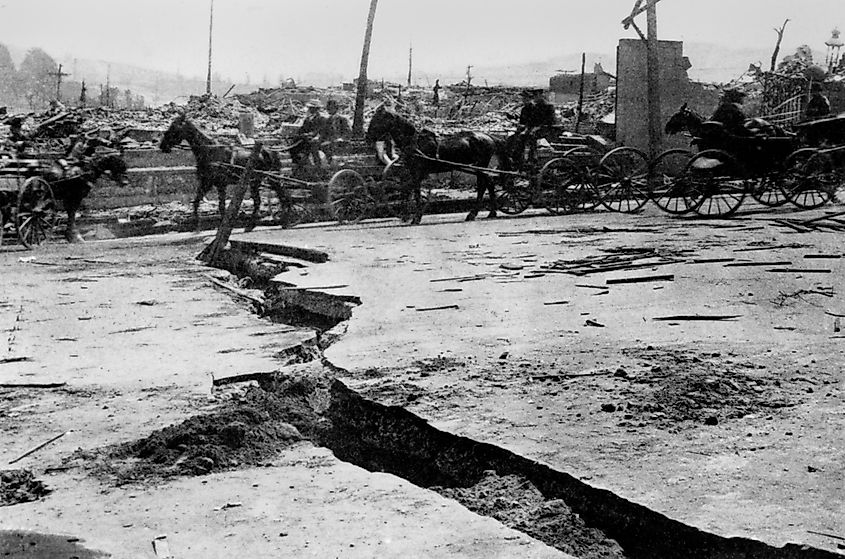

Though that might not sound like much, the cumulative movement over decades—or centuries—can lead to sudden, violent shifts. In fact, during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, parts of the fault shifted an astonishing 6.4 meters (21 feet) almost instantly.

The Anatomy of the Fault

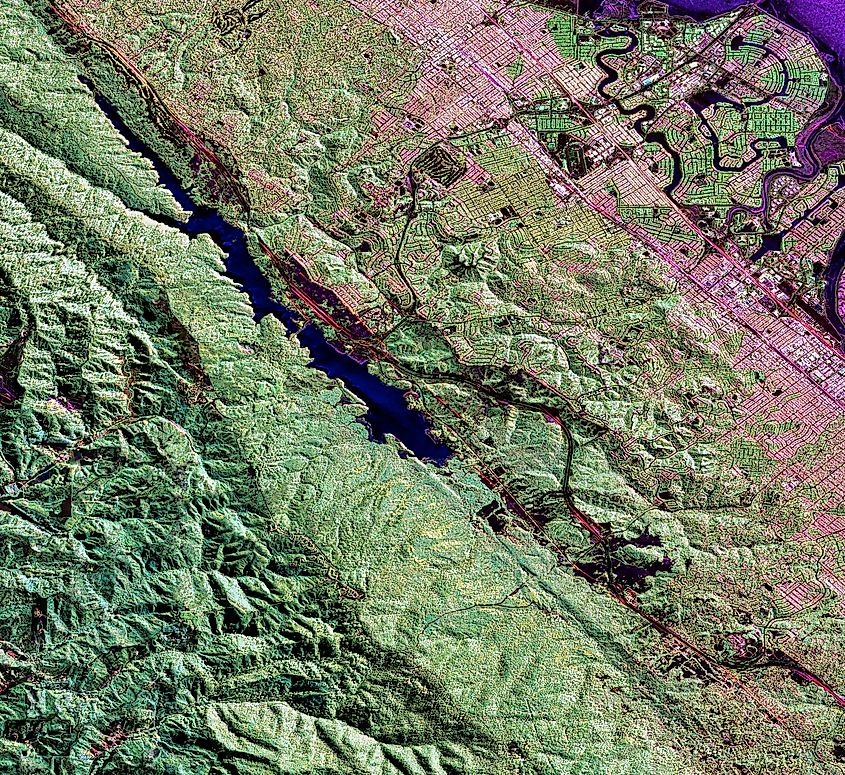

From a traveler’s perspective, the San Andreas Fault is a subtle presence in the landscape. You won’t find gaping chasms or dramatic cliffs in most areas. Instead, it often looks like a series of ridges, sag ponds, or oddly offset streams. But make no mistake—the fault is there, slicing through deserts, cities, forests, and farmland.

Here’s a breakdown of how the fault divides California:

-

Southern Section: Begins near the Salton Sea and extends north through Palm Springs and the San Bernardino Mountains.

-

Central Section: Passes through sparsely populated areas like the Carrizo Plain, where the fault is most visibly defined.

-

Northern Section: Runs near major cities like San Jose and San Francisco before dipping into the Pacific Ocean.

Perhaps most alarmingly, millions of Californians live near or directly on top of the fault. Some cities have neighborhoods, streets, and even homes built right along its path. In the Bay Area, the BART subway system runs directly through the fault zone, making earthquake preparedness a necessity, not a luxury.

Famous Earthquakes Along the San Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is responsible for some of the most significant earthquakes in US history. While it is not the only fault in California, it’s certainly the most well-known.

The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

On April 18, 1906, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake struck San Francisco, killing over 3,000 people and leveling much of the city. The shaking and subsequent fires destroyed more than 80% of San Francisco’s buildings. To this day, the 1906 earthquake remains one of the most devastating natural disasters in American history.

The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake

Also known as the “World Series Earthquake,” this magnitude 6.9 quake occurred on October 17, 1989, during a live broadcast of the World Series. Though not as deadly as the 1906 event, it caused widespread damage in the San Francisco Bay Area and killed 63 people.

The 1994 Northridge Earthquake

While not directly on the San Andreas Fault, the Northridge Earthquake (magnitude 6.7) occurred along one of its larger secondary faults. The shaking heavily impacted Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley, caused 57 deaths, and inflicted an estimated $20 billion in damage.

Why Earthquakes Are Inevitable

Earthquakes in California are not a matter of if, but when. The San Andreas Fault has a long history of seismic activity and is overdue for another major rupture, especially in the southern section near Los Angeles, which hasn’t experienced a major quake in more than 300 years.

Scientists use the term "The Big One" to describe a hypothetical future quake that could reach magnitude 7.8 or higher, potentially striking a heavily populated area. Such an event could result in thousands of deaths and severe infrastructure damage.

Living on the Fault Line: Risk and Resilience

Despite the risks, California continues to grow. Today, about three-quarters of California’s population lives within 30 miles of the San Andreas Fault. That’s more than 30 million people living in earthquake territory.

Recognizing the danger, California has become a global leader in earthquake preparedness and infrastructure resilience. Modern building codes require structures to absorb seismic shocks. Roads, bridges, and public transit systems like BART have been reinforced to reduce collapse risks. Additionally, California is investing in early warning systems like ShakeAlert, which sends alerts seconds before shaking begins—enough time to take cover or halt trains.

Can You Visit the San Andreas Fault?

For geology enthusiasts and travelers with a curious streak, the San Andreas Fault offers several opportunities to see the landscape it has shaped. Some highlights include:

-

Carrizo Plain National Monument: Located in central California, this remote area has one of the most visible sections of the fault. Visitors can see offset stream beds and fault scarps that clearly show tectonic movement.

-

Parkfield: Known as the "Earthquake Capital of the World," this tiny town sits right on the fault and hosts an earthquake observatory.

-

Palm Springs Area: Several guided tours take visitors along the southern portion of the fault, often combined with jeep excursions into desert canyons.

-

Point Reyes National Seashore: Just north of San Francisco, this coastal park offers hiking trails that cross the fault, with interpretive signs explaining its significance.

Why the San Andreas Fault Matters—Far Beyond California

While the San Andreas Fault is mostly confined to California, its significance extends far beyond state lines. It’s one of the most studied faults in the world, offering key insights into plate tectonics, earthquake prediction, and disaster preparedness. The research done here informs building practices and emergency planning globally, especially in other seismically active regions.

Moreover, the San Andreas Fault is a stark reminder of Earth’s dynamic nature. It challenges humanity to adapt—to engineer safer cities, educate residents, and prepare for the unpredictable.

Final Thoughts

The San Andreas Fault isn’t just a crack in the ground; it’s a fundamental part of California’s identity. It shapes its mountains, defines its landscapes, and reminds us of the powerful forces beneath our feet. As cities expand and the population grows, understanding and respecting this fault becomes more important than ever.

Whether you’re hiking along its scarps or riding a subway through its zone, the San Andreas Fault is a silent presence—always shifting, always watching. For California, it’s both a geological marvel and a ticking clock.

Quick Facts About the San Andreas Fault

-

Length: Over 800 miles (1,300 kilometers)

-

Type: Transform fault (strike-slip)

-

Plates Involved: Pacific Plate and North American Plate

-

Average Movement: 4–6 cm (1.6–2.4 inches) per year

-

Major Earthquakes: 1906 San Francisco, 1989 Loma Prieta, 1994 Northridge (secondary fault)

-

Visible Locations: Carrizo Plain, Parkfield, Point Reyes, Palm Springs

FAQ

Can the San Andreas Fault cause a tsunami?

Not directly. Strike-slip faults like the San Andreas mostly move horizontally, which typically does not displace enough water to generate tsunamis. However, underwater landslides triggered by an earthquake could potentially cause localized tsunami effects.

Is it safe to live near the San Andreas Fault?

While there is always risk, California has some of the world’s most advanced earthquake building codes and emergency systems. Being informed and prepared is key to living safely near the fault.

What’s “The Big One”?

“The Big One” refers to a potential future earthquake along the San Andreas Fault, especially in the southern segment, that could reach magnitude 7.8 or higher. Scientists believe it is likely within the next several decades.

Can scientists predict when an earthquake will occur?

Not precisely. Scientists can estimate probabilities over timeframes but cannot predict the exact date or time of an earthquake.