The Largest Coral Reef in the United States

Beneath the turquoise waters off South Florida, a sprawling underwater world unfolds, teeming with life and color. Stretching 168 miles along the edge of the Florida Keys, the Florida Reef (also known as the Great Florida Reef) is the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States. It forms an arc just offshore, tracing the Keys from Biscayne National Park to the Marquesas Keys, creating a marine landscape so vast and intricate it rivals anything in the Caribbean.

This colossal ecosystem encompasses more than 6,000 individual reefs and supports over 500 species of fish, 45 types of stony coral, and 35 kinds of octocorals. It’s a living city beneath the waves, built not by human hands but by billions of tiny coral polyps that have worked continuously for thousands of years to create one of North America’s most remarkable natural wonders.

A Reef that Defines Florida’s Waters

The Florida Reef stretches like a luminous necklace beneath the surface, mirroring the gentle curve of the Keys themselves. Its northern reach begins in Biscayne National Park, where clear waters meet mangrove coastlines, and extends westward toward the Marquesas Keys, just beyond Key West. Along the way, it passes through protected sanctuaries like John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park (the first underwater park in the United States) and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, which together safeguard much of this marine treasure.

Geologically speaking, this reef is a product of time and transformation. It began forming between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago, as sea levels rose following the end of the last Ice Age. Ancient coral colonies gradually built up layers of calcium carbonate, their skeletons fusing into the limestone framework that underpins the Keys and their surrounding waters. Today, this ancient architecture continues to grow, providing structure for new life even as modern threats press in from every direction.

A Living Mosaic Beneath the Waves

The Florida Reef is more than a single coral wall. It’s a network of distinct ecosystems layered across the seafloor, each with its own personality and cast of marine characters.

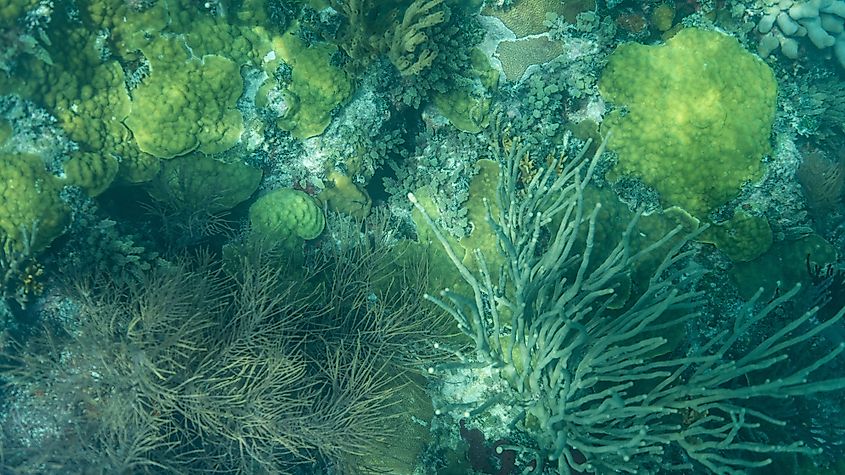

Closest to the Keys lies the hardbottom community, where sea fans, stony corals, and algae colonize limestone bedrock. Here, small but hardy corals anchor the ecosystem, creating shelter for crustaceans, mollusks, and reef fish like grunts, groupers, and barracuda.

Further offshore, the patch reefs begin to rise. These smaller reef clusters form in shallow water, often appearing like domes scattered across the sandy bottom. Many of them, including the well-known Hen and Chickens Reef, are teeming with life. Star corals and brain corals dominate the structure, while parrotfish, angelfish, and trumpetfish dart through the coral heads.

Beyond these lie the bank reefs, the grand outer ridges of the Florida Reef. These formations rise along the edge of the Florida Straits, where the water deepens and the ocean’s pulse grows stronger. The outer reefs are defined by dramatic spur-and-groove formations or ridges of coral separated by sandy channels carved by waves and currents. In the shallows, fire corals and elkhorn corals dominate, giving way to star and plate corals in deeper zones. This complex structure provides habitat for large reef fish, from queen triggerfish to parrotfish and snappers.

A Hotspot of Biodiversity

Despite being near the northern limit for tropical coral growth, the Florida Reef rivals Caribbean reefs in diversity. Nearly 1,400 species of marine life have been documented here, from sea urchins and sea cucumbers to dolphins and sea turtles. Schools of yellowtail snapper swirl through coral valleys while eagle rays glide overhead. Spiny lobsters crawl among coral crevices, and nurse sharks nap beneath coral ledges.

The reef’s proximity to the Florida Current (a powerful ocean stream that merges with the Gulf Stream) brings warm, nutrient-rich water to the ecosystem, fueling its productivity. That same current, however, has also made the reef historically treacherous for navigation. Over the centuries, hundreds of ships wrecked along these hidden coral ridges, leaving behind stories that remain part of Keys lore today.

The Coral Crisis

Like reefs around the world, the Florida Reef faces a battle for survival. In the past half-century, this underwater wonder has endured an alarming decline. By the late 2010s, scientists with NOAA estimated that only about 2% of the reef’s original coral cover remained. The culprits are many: pollution, overfishing, disease, and the impacts of climate change.

Ocean warming poses the most immediate threat. Even a small rise in temperature can cause coral bleaching, a stress response where corals expel the algae that provide them with color and nutrients. Without these algae, corals turn ghostly white and struggle to survive. In July 2023, record-breaking heat in Florida’s coastal waters triggered one of the most severe bleaching events ever recorded, killing vast sections of reef.

Coral disease compounds the crisis. Outbreaks of white band disease and stony coral tissue loss disease have devastated populations of iconic corals such as elkhorn and staghorn. These branching corals once dominated the reef’s landscape but have declined by over 90 percent since the 1980s.

Other stressors include rising sea levels, sedimentation from coastal development, and microplastic pollution. Even the long-spined sea urchins that once kept algae growth in check suffered massive die-offs in the 1980s, allowing seaweed to overtake coral surfaces.

Science and Hope Beneath the Surface

Despite these challenges, hope persists. Across the Keys, scientists and conservationists are working to restore the reef one coral fragment at a time. In 2025, large-scale coral planting began in several locations throughout the Florida Keys, using nursery-grown corals cultivated in protected environments. Once mature, these corals are transplanted to degraded reef sections, where they can grow and reproduce naturally.

One of the most ambitious efforts is NOAA’s Mission: Iconic Reefs, an initiative to restore nearly 3 million square feet of coral habitat across seven key reef sites by 2040. This long-term project involves planting resilient coral species, removing invasive algae, and monitoring growth over decades to ensure survival.

Researchers at the Florida Aquarium and the University of South Florida have also launched a groundbreaking program to develop heat-tolerant corals. Thousands of juvenile elkhorn corals, bred to withstand warmer ocean temperatures, are now being tested in special tanks before being introduced to the wild. Even if only a fraction survive, each new coral adds genetic diversity and resilience to the reef’s population.

Meanwhile, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission is testing an innovative device called the Coral Defender, designed to shield young corals from predators as they mature on the reef. Early results have shown a marked increase in coral survival rates.

Protecting a Living Shield

Beyond its ecological importance, the Florida Reef plays a vital protective role. Acting as a natural barrier, it absorbs the force of waves and storm surges, reducing erosion and safeguarding the Florida Keys from the full brunt of hurricanes. Its health is directly tied to the well-being of coastal communities and local economies.

Recreation and tourism also depend heavily on this ecosystem. According to state data, reef-related activities such as snorkeling, diving, and fishing generate billions of dollars annually for South Florida, supporting tens of thousands of jobs. The reefs’ economic and cultural value make their protection not just an environmental priority, but an economic one as well.

Echoes of History

The Florida Reef has long shaped the human story of the Keys. In the 1800s, it was both a peril and a livelihood. Countless ships ran aground on its coral heads, their cargoes salvaged by skilled wreckers from Key West. These shipwrecks led to the construction of towering lighthouses that still stand today, their iron skeletons guarding the passage once feared by sailors.

Over time, growing concern for the reef’s decline led to a wave of conservation milestones. John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park was established in 1960 as the nation’s first underwater park. Biscayne National Park followed in 1968, and in 1990, the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary was created, bringing the entire reef system under coordinated federal and state protection.

A Living Legacy

The Florida Reef is more than a natural wonder; it is a living record of endurance and change. It has survived ice ages, hurricanes, and centuries of human activity. Its coral skeletons tell stories written over millennia.

In an era of rising seas and warming waters, the reef’s future depends on science, stewardship, and global cooperation. Restoration efforts, genetic innovation, and protected sanctuaries are helping turn the tide. With persistence and care, this vast coral network may yet continue to thrive, shimmering beneath the surface as the nation’s largest and most vital living reef.

The Great Florida Reef remains one of America’s most dazzling natural treasures. A labyrinth of color and life that connects history, ecology, and the unrelenting rhythm of the sea.

Quick Facts: The Florida Reef

-

Extends 168 miles from Biscayne National Park to the Marquesas Keys

-

Only living coral barrier reef in the continental US

-

Home to 1,400 marine species, including 500 species of fish

-

Estimated to be 5,000 to 7,000 years old

-

Restoration efforts aim to rebuild 3 million square feet of coral habitat by 2040