US States That Make up The Great Basin

The Great Basin stands apart from every other major geographic region in the United States. No rivers reach the ocean here. Water flows inward, pooling into salt flats, desert lakes, and ancient basins shaped by time, tectonics, and climate. This vast interior landscape defines much of the American West. It covers nearly 210,000 square miles and stretches across multiple states. Understanding which states belong to the Great Basin reveals geography, and a story of isolation, adaptation, and striking natural contrast.

These seven US states make up the Great Basin. Learn what qualifies land as part of the basin and what makes each state’s portion unique.

States That Make Up The Great Basin

| State | Percentage of State in the Great Basin | Notable Features | Key Water Bodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nevada | About 85% | Basin and Range terrain, Great Basin National Park | Pyramid Lake, Walker Lake |

| Utah | About 40% | Great Salt Lake, Bonneville Salt Flats | Great Salt Lake, Sevier Lake |

| California | About 15% | Owens Valley, Mono Basin, high elevation deserts | Mono Lake, Owens Lake |

| Oregon | About 20% | High desert plateaus, volcanic landscapes | Summer Lake, Warner Lakes |

| Idaho | About 5% | Southern desert basins | Bear Lake |

| Wyoming | Less than 10% | Great Divide Basin | Ephemeral playas |

| Colorado | Under 1% | Isolated closed basins | Seasonal wetlands |

What Defines the Great Basin?

Bristlecone-Glacier Trail. Editorial credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Great Basin is a hydrologic region rather than a political or cultural one. Its defining feature is internal drainage. Rain and snowmelt stay trapped within the region instead of flowing to the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf, or the Atlantic. Water ends in playas, salt lakes, or underground aquifers.

Mountain ranges and basins repeat across the landscape in a pattern created by tectonic stretching. These north to south ranges trap precipitation and create rain shadows that sustain deserts, sagebrush plains, and alpine environments in close proximity.

Elevation plays a key role. Many valleys sit above 4,000 feet, and the surrounding peaks rise well above 10,000. This vertical relief allows snowpack, glaciers in the distant past, and surprisingly diverse ecosystems to exist within a desert framework.

Nevada: The Core of the Great Basin

Nevada holds the largest share of the Great Basin and defines its character more than any other state. Nearly the entire state lies within the basin, making Nevada the only state where most the water never reaches the sea.

Nevada’s terrain consists of long, narrow mountain ranges separated by wide valleys. Great Basin National Park near the Utah border showcases the region’s extremes, with ancient bristlecone pines, limestone caves, and peaks rising above 13,000 feet.

Streams disappear into desert floors, and lakes such as Pyramid Lake and Walker Lake survive only through careful water balance. Seasonal snowmelt provides much of the region’s moisture, supporting ranching, wildlife, and human settlement.

Indigenous communities thrived here long before statehood, adapting to scarce water and wide open land. Mining booms later shaped Nevada’s towns, transportation routes, and population centers, many of which still depend on groundwater today.

Utah: Mountains, Salt, and Closed Basins

Western Utah forms a major portion of the Great Basin, offering some of its most recognizable features.

The Great Salt Lake represents the largest remnant of ancient Lake Bonneville, a massive Ice Age lake that once covered much of Utah. As the climate warmed, the lake shrank, leaving behind salt flats, shorelines, and mineral-rich sediments.

Utah’s Great Basin landscape transitions quickly between dry valleys and high mountain ranges. Snowfall in the Wasatch and surrounding ranges feeds groundwater systems that sustain agriculture and growing urban areas along the basin’s edge.

Salt flats such as Bonneville provide valuable insight into past climates and tectonic movement. These wide open expanses also play a role in aviation testing, land speed records, and atmospheric research.

California: The Eastern Desert Interior

Eastern California contains a significant portion of the Great Basin, sharply contrasting with the coastal image often associated with the state.

Owens Valley lies between the Sierra Nevada and the White Mountains, forming a classic Great Basin landscape. Mono Lake, with its distinctive tufa towers and saline waters, exemplifies internal drainage at work.

Los Angeles aqueduct projects redirected water away from Owens Valley in the early 20th century, reshaping ecosystems and sparking some of the most famous water conflicts in US history. These events helped define modern water policy across the West.

California’s Great Basin territory sits near both the highest and lowest points in the contiguous United States. This dramatic elevation change creates stark scenery and extreme climate variation within short distances.

Oregon: The High Desert Corner

Southeastern Oregon contributes a lesser known but equally striking section of the Great Basin.

Ancient lava flows, cinder cones, and fault-block mountains define much of this region. Crater Lake lies outside the Great Basin, but nearby desert basins share volcanic origins tied to regional tectonic forces.

Large tracts of public land support pronghorn antelope, sage grouse, and migratory birds that depend on seasonal wetlands. Remote geography keeps population density low, preserving wide open desert views.

Cold winters and hot summers define Oregon’s Great Basin climate. Snowmelt supports ranching operations that rely on shallow groundwater and ephemeral streams.

Idaho: The Southern Basin Extension

Southern Idaho forms a small but important extension of the Great Basin.

Most of Idaho drains into the Snake River system, which flows toward the Columbia River and the Pacific. Southern portions near the Utah and Nevada borders break this pattern, falling within closed Great Basin watersheds.

Irrigation plays a major role here, allowing crops to thrive in arid valleys. Water management strategies reflect the same challenges seen across the basin, balancing limited supply with growing demand.

Idaho’s Great Basin territory bridges true desert landscapes and the broader Intermountain West, offering insight into how drainage boundaries shift across the region.

Wyoming: A Small but Significant Slice

Southwestern Wyoming includes a limited portion of the Great Basin, often overlooked due to the state’s association with the Rockies and Great Plains.

This unique area features a topographic basin where water drains neither east nor west. Rain and snowmelt evaporate or seep into the ground instead of flowing toward any ocean.

The Great Divide Basin challenges the idea of a single Continental Divide line. Its presence highlights the complexity of North America’s drainage systems and elevates Wyoming’s role in Great Basin geography.

Harsh conditions and limited water keep development minimal, preserving the basin’s raw, open character.

Colorado: The Eastern Fringe

A very small portion of western Colorado touches the Great Basin through isolated internal drainage areas.

Most of Colorado sends water toward the Colorado River or the Great Plains. Tiny closed basins near the Utah border mark the easternmost reach of Great Basin hydrology.

These areas help researchers study how climate, elevation, and geology influence drainage patterns across state lines.

Why the Great Basin Matters Today

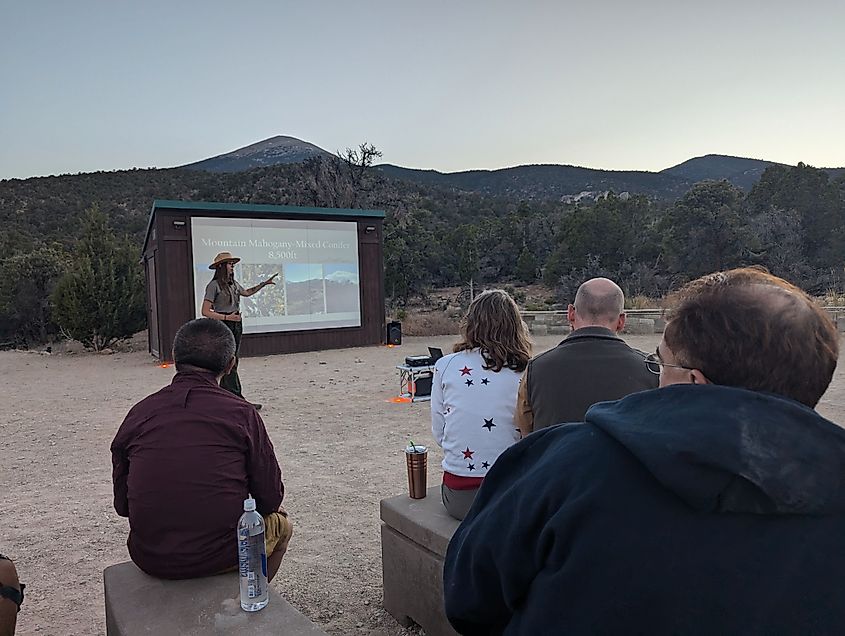

Astronomy Amphitheater, Great Basin National Park. Editorial credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The Great Basin plays a growing role in conversations about water scarcity, climate change, and land use in the American West. Its closed drainage systems make it especially sensitive to drought, overuse, and shifting precipitation patterns.

Urban growth near basin edges places increasing pressure on groundwater. Agricultural communities depend on careful management to maintain productivity. Wildlife migration routes rely on shrinking wetlands and seasonal water sources.

The region also holds cultural significance. Indigenous histories, pioneer trails, mining towns, and modern conservation efforts all intersect across the basin’s valleys and ranges.

A Region Defined by Boundaries and Extremes

Teresa Lake, Great Basin National Park. Editorial credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Great Basin stretches across Nevada, Utah, California, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and a small part of Colorado, unified by water that never reaches the sea. Each state contributes a distinct chapter to the basin’s story, shaped by geology, climate, and human adaptation.

Mountains rise sharply above desert floors. Salt flats replace rivers. Lakes appear and vanish with changing climate cycles. This combination of isolation and diversity gives the Great Basin its enduring fascination.

Understanding which states make up the Great Basin offers more than a map lesson. It provides insight into how landforms shape history, how water defines survival, and how one of America’s most underrated regions continues to influence the West.