Great Basin Desert

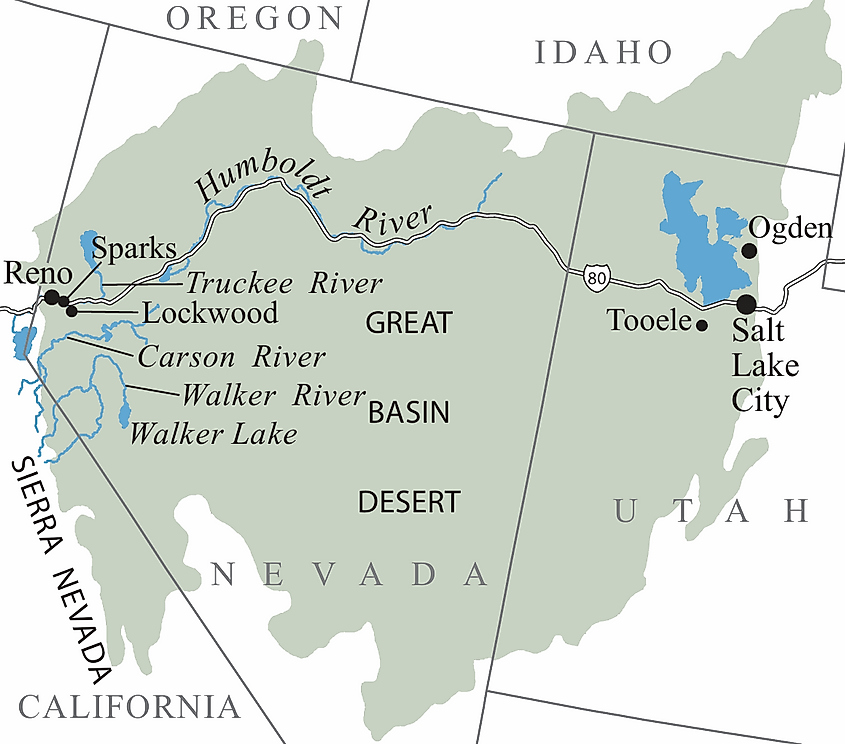

The Great Basin Desert lies within the Great Basin, located between the Sierra Nevada and the Wasatch Range in the western United States. This desert largely overlaps with the Great Basin shrub steppe as defined by the World Wildlife Fund, and it coincides with the Central Basin and Range ecoregion identified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Geological Survey. It is a temperate desert characterized by hot, dry summers and snowy winters.

The Great Basin Desert stretches over vast areas of Nevada and Utah and extends into eastern California. Along with the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan Deserts, it is one of the four deserts in North America that have been defined on biological grounds.

Geography and Climate

Definitions of the Great Basin Desert differ. Some scholars define it by the absence of creosote bush, while others rely on ecoregion boundaries. The EPA formerly labeled much of this region as Northern Basin and Range, later renaming it Central Basin and Range. The World Wildlife Fund employs similar limits, calling part of it the Great Basin Shrub Steppe. Regardless of minor boundary differences, the region’s ecology spans valleys, mid-slope woodlands, and higher mountains with distinct species in each zone.

Characterized by basin and range topography, it contains broad valleys bordered by parallel mountain ranges oriented north–south. Over thirty-three peaks exceed 9,800 feet, while many valleys are above 3,900 feet. This steep elevation gradient fosters diverse habitats, from salty dry lakes in basins to sagebrush communities and pinyon-juniper forests higher up. The variation creates numerous isolated populations of plants and animals, including more than six hundred vertebrate species. Sixty-three are considered at risk, chiefly due to shrinking habitats.

Its climate reflects the positioning between two major mountain systems. The Sierra Nevada blocks moisture from the Pacific, while the Rocky Mountains limit flow from the Gulf of Mexico. Pleistocene lakes, such as Lahontan and Bonneville, influenced local salinity and alkalinity when they evaporated at the end of the last ice age. Precipitation differs across the desert, typically lower in western basins closest to the Sierra Nevada.

Summers here are hot and dry, with daytime highs often topping 90°F, while winter temperatures can be bitterly cold, especially in mountainous areas. This makes it the coldest desert in North America. Most precipitation that reaches the region falls as snow or rain on mountains, with little escaping to the ocean. Instead, water evaporates or accumulates in ephemeral lakes.

Biological Communities

Multiple biological communities exist across these elevations. Saline conditions in the lowest basins form playas with sparse vegetation, though shadscale or greasewood appear at edges. Slightly higher elevations host extensive sagebrush stands, featuring big sagebrush in less saline soils and black sagebrush on rockier ground. Above about 6,000 feet, pinyon-juniper forests emerge, with low pines, junipers, and an understory of sagebrush. Montane forests, such as those of Douglas fir or bristlecone pine, occupy even cooler areas. Above the treeline, alpine zones support hardy grasses and wildflowers. Streams and rivers create riparian corridors, marked by willows and cottonwoods, that thread through different elevations.

Valley floors host ephemeral streams, and their riparian zones provide breeding grounds for amphibians and habitat for beavers. Volcanic hills often harbor black sagebrush, while big sagebrush tends to dominate alluvial fans. In higher elevations, conifer forests feature well-adapted pines that can withstand harsh winters and survive for centuries atop wind-swept ridges. Bighorn sheep thrived.

Many subdivisions exist within the desert, categorized by the EPA at Level IV. These include salt desert zones like the Bonneville Salt Flats, shadscale-dominated basins, and ancient lakebeds or playas. Some slopes benefit from moisture off the Sierra Nevada, leading to denser vegetation. Others remain more arid and contain specialized salt-tolerant species. Certain “sky islands” feature isolated high-elevation ranges with species found nowhere else, underscoring the region’s biodiversity.

Human activities such as groundwater pumping, farming, fires, grazing, and mining have significantly impacted the Great Basin Desert. Numerous rare or endangered organisms, including the Ute ladies’-tresses orchid and endemic fishes, reflect the vulnerability of this high desert ecosystem. Genetic isolation on separate mountain peaks further raises conservation concerns. Yet the region persists as a natural laboratory of survival, where plants and animals withstand wide temperature swings, limited precipitation, and dramatic terrain. Great Basin National Park highlights these extremes, allowing visitors to witness how life has adapted amid such challenging conditions.