National Forest vs National Park: What’s the Difference?

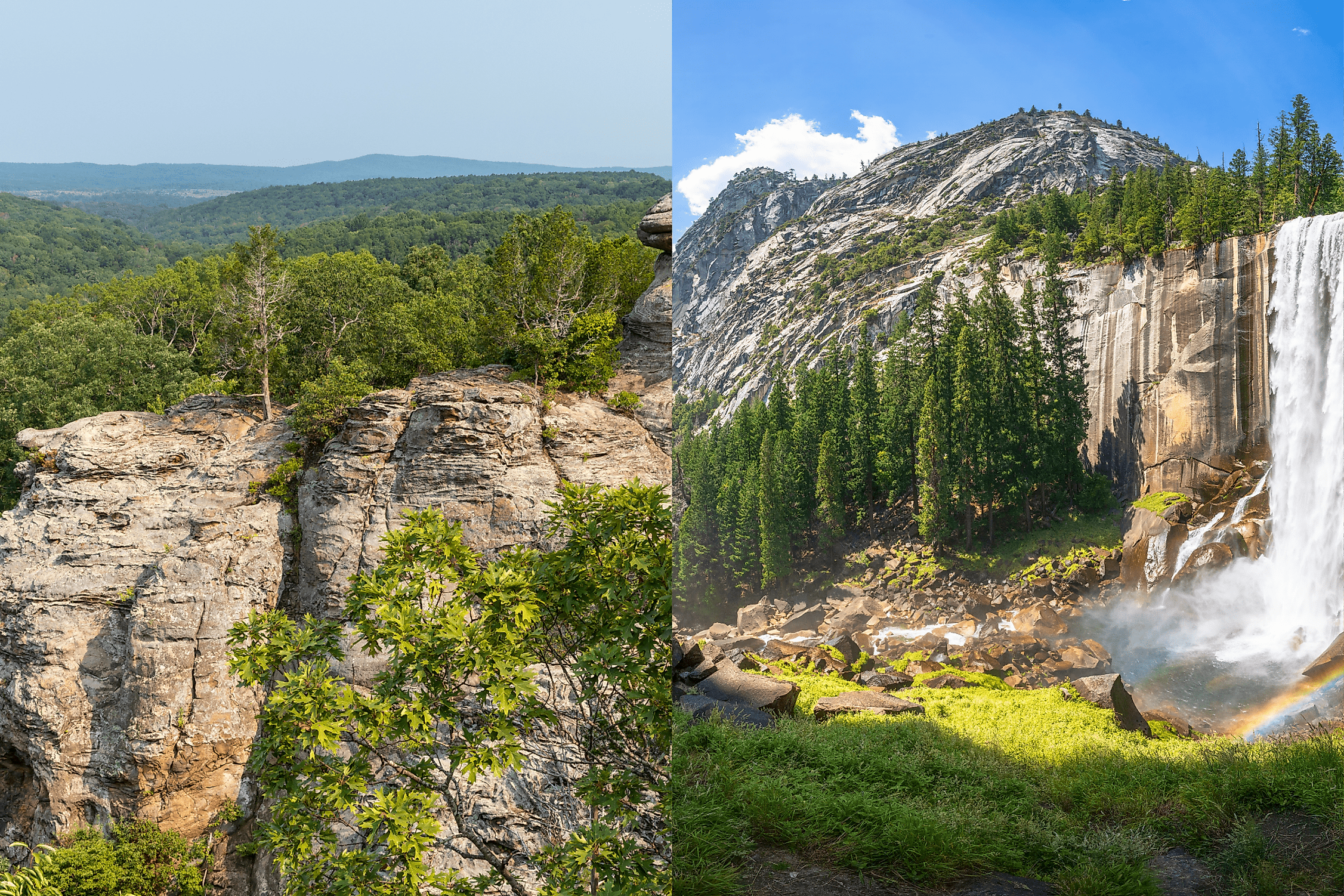

America’s public lands often blur together in the imagination. Towering peaks, endless trees, wildlife roaming freely, and miles of open sky appear in both national parks and national forests. At a glance, the two seem interchangeable. A closer look reveals a meaningful divide shaped by history, purpose, and how each landscape is managed day to day.

Understanding the difference between a national forest and a national park adds depth to any road trip, hike, or scenic drive. It also explains why camping rules change across boundaries, why some lands support grazing or logging, and why others remain tightly protected. These distinctions shape how millions of acres are used, preserved, and experienced across the United States.

Two Systems, Two Histories

The roots of national parks and national forests stretch back to different moments in American history, each responding to a distinct national need.

National parks came first

In 1872, Yellowstone became the world’s first national park, setting aside a vast landscape for preservation and public enjoyment. The idea was radical at the time. Land would be protected not for profit or settlement but for its natural wonders and future generations. That philosophy expanded with the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, a single agency tasked with managing these special places.

National forests followed a different path

In 1891, the Forest Reserve Act gave the president authority to establish forest reserves. These lands addressed a growing concern that America’s timber resources were being depleted too quickly. Shoshone National Forest, originally part of the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, marked an early example of this approach. In 1905, management of forest reserves shifted from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture, leading to the creation of the U.S. Forest Service.

From the start, national forests focused on balance rather than strict preservation. That mission still defines them today.

Who Manages the Land

Management plays a central role in how these landscapes function.

National parks fall under the Department of the Interior and are managed by the National Park Service. This agency oversees not only national parks but also monuments, seashores, lakeshores, historic sites, and more.

National forests operate under the Department of Agriculture through the U.S. Forest Service. This distinction may seem subtle, though it reflects a major philosophical difference. The Forest Service treats land as a renewable resource that must be carefully managed to meet multiple needs over time.

That difference influences everything from trail maintenance to fire management to permitted land uses.

Preservation vs Multiple Use

Mission statements reveal the clearest contrast between national forests and national parks.

The National Park Service aims to preserve natural and cultural resources in an unimpaired state. Protection comes first. Recreation, education, and inspiration follow within carefully defined limits. Landscapes in national parks change slowly, guided by ecological processes rather than economic activity.

National forests operate under a multiple use mandate. The U.S. Forest Service manages land to support recreation, timber harvesting, grazing, wildlife habitat, and watershed protection. Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service, famously described this philosophy as providing the greatest good for the greatest number over the long run.

That mission allows national forests to adapt to changing needs while remaining public land. Hiking trails may pass active grazing allotments. Scenic drives may cut through working forests. Snowmobiling, mountain biking, and hunting often coexist alongside wilderness areas.

Size and Scope of Each System

The scale of these two systems often surprises people.

- The National Forest System covers roughly 193 million acres, making it the larger of the two. This includes 155 national forests, 20 national grasslands, and one national tallgrass prairie. These lands stretch across nearly every state, often surrounding or connecting more famous protected areas.

- The National Park System spans about 84 million acres, more than half of which lies in Alaska. While only 63 sites officially carry the title of national park, the system includes nearly 400 areas in total. National monuments, battlefields, historic parks, scenic rivers, seashores, and trails all fall under the same umbrella.

Both systems reach deep into American geography, though national forests quietly dominate in sheer acreage.

Recreation Rules and Access

Outdoor recreation looks different depending on which side of the boundary a visitor enters.

National parks prioritize low impact recreation

Hiking, wildlife viewing, photography, and ranger programs define the experience. Backcountry access often requires permits, and campgrounds follow strict rules to protect fragile ecosystems.

National forests allow a wider range of activities

Dispersed camping often requires no reservation. Hunting and fishing are common. Off-highway vehicles, mountain bikes, and snowmobiles have designated areas. Some forests even permit firewood collection or seasonal grazing.

This flexibility makes national forests feel less regulated and more open-ended, though it also requires visitors to take greater responsibility for safety and stewardship.

Wilderness Areas Within Both

Wilderness areas add another layer of complexity.

Congress can designate wilderness areas within national parks, national forests, wildlife refuges, or Bureau of Land Management lands. These places receive the highest level of protection under the Wilderness Act of 1964.

Motorized equipment, roads, and development are prohibited. Trails remain primitive. The goal is to preserve landscapes as close to untouched as possible.

A single national forest may contain vast wilderness areas alongside actively managed sections. A national park may protect wilderness at its core while offering developed access points around the edges.

Beyond Parks and Forests

America’s public lands extend far beyond these two categories.

National wildlife refuges protect habitats critical to fish, birds, and other wildlife. National conservation areas safeguard landscapes with scientific, cultural, or scenic importance. National monuments preserve specific features, often designated quickly to protect threatened resources.

Historic sites, memorials, and battlefields focus on human stories rather than natural ones. National recreation areas emphasize water based activities around reservoirs. Wild and scenic rivers protect free flowing waterways. Seashores and lakeshores preserve coastlines and freshwater shores. National trails stitch landscapes together across state lines.

National parks and national forests represent just two threads in a much larger tapestry of public land designations.

Why the Difference Matters

Understanding these distinctions shapes expectations.

Travelers entering a national park often find entrance fees, structured visitor centers, and carefully planned infrastructure. Experiences feel curated and iconic. Landscapes are protected with precision.

Those stepping into a national forest encounter a different rhythm. Roads may be rougher. Signage may be sparse. Freedom expands, along with responsibility. Adventures unfold more spontaneously.

Neither approach is better. Each reflects a different vision of public land stewardship. Together, they offer a remarkable range of experiences that few countries can match.

Choosing Where to Go

Deciding between a national park and a national forest depends on travel style.

- National parks shine for first time visitors, photographers, and those drawn to famous landmarks. They offer accessibility, interpretation, and dramatic scenery concentrated into defined areas.

- National forests reward explorers who enjoy flexibility. Solitude often comes easier. Campsites feel more personal. Trails stretch deeper into lesser-known terrain.

Many of the best trips blend both. Forest roads often lead to park entrances. Wilderness corridors cross administrative lines. America’s public lands work best as a connected system rather than isolated units.

The Shared Legacy

National forests and national parks reflect different answers to the same question. How should a nation care for its land?

One answer emphasizes preservation above all else. The other balances use and protection across generations. Both philosophies emerged from the same belief that public land belongs to everyone.

That shared legacy continues to shape millions of acres, countless adventures, and an enduring connection between people and place.