Susan B. Anthony: The Woman Behind the 19th Amendment

Susan B. Anthony’s name is synonymous with the fight for women’s suffrage in the United States. Though she never lived to see the fruits of her labor realized in her lifetime, her efforts laid the foundation for the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which granted American women the right to vote. Her activism spanned more than five decades and transformed the landscape of American politics, law, and gender equality.

Born into a Quaker family steeped in ideals of justice and moral clarity, Anthony became one of the most visible and unyielding advocates for civil rights in the 19th century. From temperance to abolition and, ultimately, to suffrage, her life was marked by a deep commitment to equity and a refusal to accept societal limits placed on women. This is the story of Susan B. Anthony: tireless organizer, suffrage pioneer, and one of the most influential figures in American history.

A Childhood Rooted in Justice

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, in Adams, Massachusetts. Raised in a devout Quaker household, Anthony absorbed values of independence, education, and social justice from a young age. Her father, a cotton mill owner and abolitionist, emphasized the importance of discipline, learning, and reform—principles that would become central to her life’s work.

By the age of three, Susan could read and write, a testament to both her intellect and her family's emphasis on education. The Anthonys relocated to Battenville, New York, in 1826, where Susan attended a local school before studying at a Quaker boarding school near Philadelphia. These early experiences gave her a front-row seat to the disparities in how women were treated, both socially and professionally.

Teaching, Temperance, and Early Activism

In 1839, Anthony took a teaching position at a Quaker seminary in New Rochelle, New York. From 1846 to 1849, she taught at a female academy in upstate New York, earning significantly less than her male counterparts. It was during these years that Anthony began to challenge the status quo of women’s roles in society.

Her initial foray into public activism came through the temperance movement—a campaign aimed at reducing alcohol consumption in America. After being denied the opportunity to speak at a temperance convention in 1852 solely because of her gender, Anthony realized that broader systemic change was needed. This experience galvanized her shift toward women's rights, and that same year she helped found the Woman’s New York State Temperance Society.

Entering the Suffrage Movement

Anthony’s growing activism brought her into contact with some of the most prominent reformers of the era, including Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and—most fatefully—Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Through this alliance, Anthony became deeply entrenched in the women’s suffrage movement.

In 1856, she became the New York agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, further intertwining the causes of abolition and women’s rights. Her advocacy also extended to married women’s property rights, which were successfully reformed in New York by 1860, thanks in part to her lobbying.

During the Civil War, Anthony co-founded the Women’s National Loyal League, which gathered hundreds of thousands of signatures supporting the abolition of slavery. But after the war, she faced disappointment. The passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments granted citizenship and voting rights to African American men but left women behind. Anthony viewed this as a betrayal, and redoubled her efforts.

Organizing, Publishing, and Pushing Boundaries

In 1868, Anthony and Stanton launched The Revolution, a periodical that gave voice to their radical ideas on equality, labor rights, and women’s suffrage. Though the paper was financially short-lived, it helped elevate the conversation around women's rights to a national platform.

The following year, Anthony and Stanton formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), distinct from the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association founded by Lucy Stone. While the latter focused on incremental reform through state legislatures, Anthony’s NWSA aimed directly at a constitutional amendment.

In 1872, Anthony put the Constitution to the test. She voted in the presidential election in Rochester, New York, arguing that the 14th Amendment gave her that right. She was promptly arrested, tried, and convicted. The judge—who had written his guilty verdict before the trial began—fined her $100. She refused to pay, and the case was dropped. But the act became a defining moment in the history of civil disobedience in America.

The Long Road to Unity and Recognition

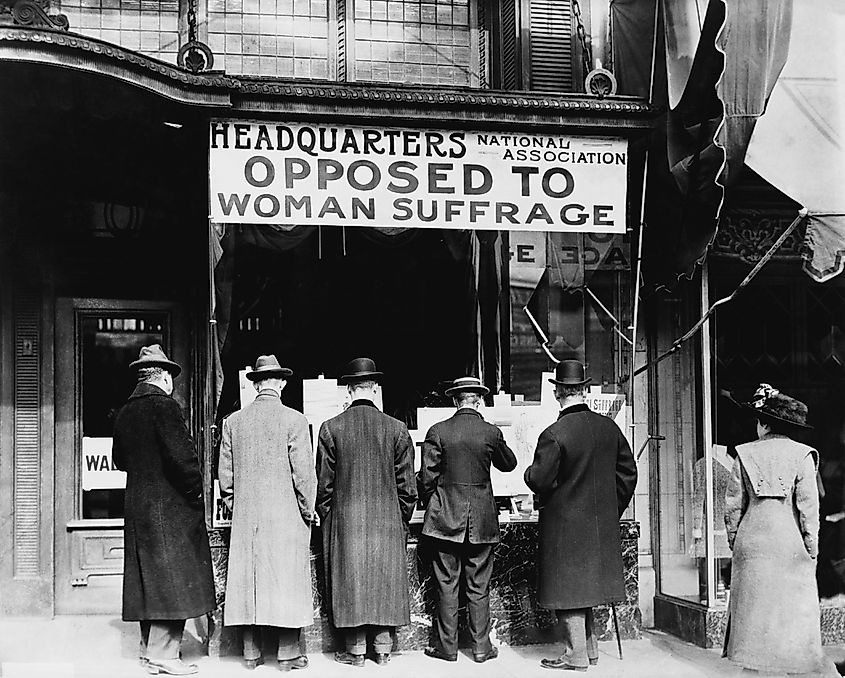

Anthony spent the next two decades traveling across the country, delivering speeches, organizing conventions, and building coalitions. She campaigned in state after state, pushing for women’s voting rights, often in the face of ridicule, legal roadblocks, and societal opposition.

In 1890, a major milestone was reached: the NWSA and AWSA merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Anthony became its president in 1892 and led the unified organization through its most crucial years. She passed the torch to her protégé, Carrie Chapman Catt, in 1900, when she was 80 years old.

During this period, Anthony also co-authored the monumental six-volume History of Woman Suffrage, preserving the movement’s legacy and intellectual foundation for future generations.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Though she retired from active leadership, Anthony remained a prominent figure nationally and internationally. She attended the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 and led the US delegation to international women’s rights conferences in London (1899) and Berlin (1904). Her stature had evolved from social agitator to elder stateswoman.

Susan B. Anthony died on March 13, 1906, in Rochester, New York—14 years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Though she never cast a legal vote, her efforts made it possible for millions of women to do so.

In 1950, she was inducted into the Hall of Fame. In 1979, she became the first woman depicted on US currency with the introduction of the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin. More recently, her legacy has stirred political and cultural debate, including a controversial presidential pardon issued in 2020 for her 1872 conviction—one she herself would have likely rejected.