Tongass National Forest

Towering trees, misty fjords, and brown bears fishing in glacier-fed streams—this isn’t the Amazon or the Pacific Northwest. It’s Alaska. More specifically, the Tongass National Forest, the largest national forest in the United States and the most expansive remaining temperate rainforest on Earth.

Spanning nearly 17 million acres across the southeastern panhandle of Alaska, the Tongass is one of America’s most ecologically important and visually stunning landscapes. Home to a complex web of ecosystems and Indigenous communities, this forest stands at the intersection of climate, conservation, and cultural heritage. But it also stands at a crossroads, as decades of logging, development, and environmental policy debates shape its future.

A Forest Born of Mountains, Glaciers, and Tides

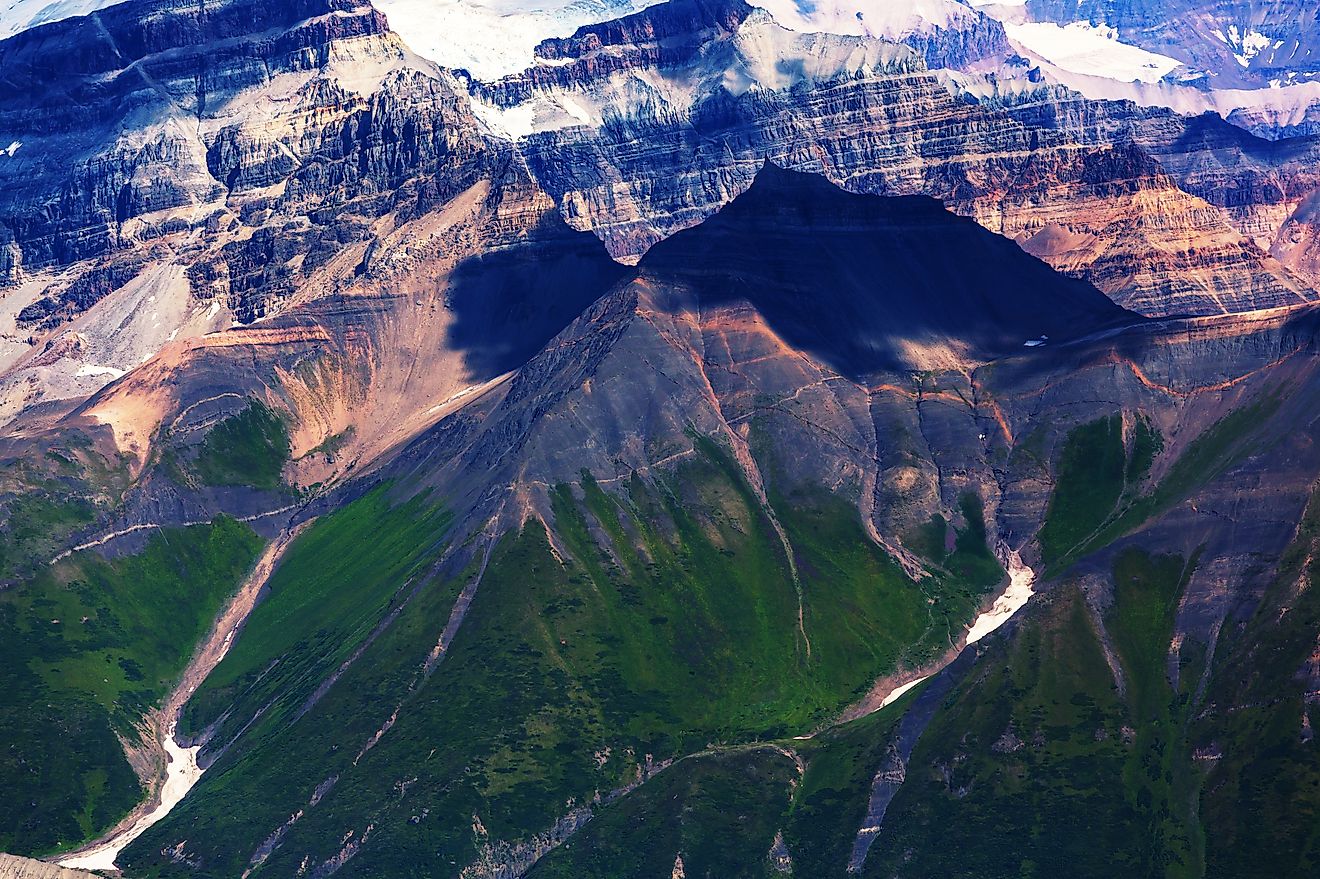

Tongass National Forest stretches some 500 miles from north to south, encompassing a sprawling network of volcanic archipelagos, rugged coastlines, deep fjords, and glacial valleys. This land of extremes boasts everything from snow-capped peaks to dense, moss-draped forests to alpine tundra above the tree line. Tidewater glaciers spill down from mountains into the sea, while old-growth trees—some centuries old—form towering cathedrals of cedar, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock.

At over 26,000 square miles, the Tongass is larger than the entire state of West Virginia. Its scale is hard to grasp unless you’ve traveled here: flying over unbroken stretches of green, where the only signs of human presence are the occasional fishing boat or remote Indigenous village.

A Living, Breathing Ecosystem

What makes the Tongass truly unique isn’t just its size—it’s what lives inside it. The forest is part of the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, and with that distinction comes extraordinary biodiversity.

Among the forest’s most iconic residents are brown bears (including grizzlies), black bears, wolves, and Sitka black-tailed deer. The rivers and streams that weave through the forest serve as breeding grounds for all five species of Pacific salmon—chinook, sockeye, coho, pink, and chum—which in turn feed everything from bald eagles to sea lions.

The Tongass is also a birdwatcher’s paradise. With the development of the Southeast Alaska Birding Trail, visitors now have access to nearly 200 curated birding locations across 18 communities. Species like the northern goshawk, red-breasted sapsucker, and the elusive marbled murrelet call this forest home. The trail’s 2023 mobile app allows birders to explore sites offline, complete with maps, checklists, and species details—offering a sustainable and accessible way to interact with the region's diverse wildlife.

A Place of Deep Cultural Roots

Long before it became a national forest, the Tongass was—and still is—home to Indigenous peoples. The Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian Nations have lived in and stewarded this land for thousands of years. The forest takes its name from a Tlingit group known as the Tongass, who have depended on its resources for food, shelter, medicine, and cultural practices.

Today, these communities continue to thrive within the Tongass, blending ancient traditions with contemporary life. Indigenous values often prioritize harmony with nature, sustainable resource use, and cultural preservation—principles that are increasingly relevant in ongoing conservation efforts.

Old-Growth Under Threat

Despite its grandeur, the Tongass is not untouched. Logging—especially industrial-scale clearcutting of old-growth trees—has altered large swaths of the forest. The most productive and biologically rich areas, filled with large, ancient trees, were often the first to be logged. In the southern half of the forest, over two-thirds of these old-growth areas have already been lost.

These losses have ripple effects. Old-growth forests are vital not just for wildlife habitat but also for carbon sequestration. In fact, the Tongass sequesters more carbon than any other forest type on Earth, playing a critical role in mitigating climate change. As global temperatures rise, preserving forests like the Tongass is increasingly seen as an ecological necessity.

Yet logging continues in many parts of the forest. The US Forest Service has long grappled with how to balance timber interests with conservation. While about one-third of the forest is protected as wilderness, roughly one-fifth remains open to commercial development. The debate between conservationists and logging advocates remains intense, especially as public interest grows in carbon-neutral and nature-based climate solutions.

The Battle for the Future

The Tongass has become a national flashpoint in environmental policy. During different presidential administrations, its fate has swung back and forth. Key among the controversies is the Roadless Rule, a federal policy that restricts road construction and logging in certain undeveloped forest areas. At times, exemptions have been granted to the Tongass, opening it up to increased logging—sparking lawsuits, protests, and nationwide debate.

Environmental advocates argue that the Tongass offers the single greatest opportunity for ecosystem-scale rainforest conservation in the face of climate change. They point out that protecting the forest could support long-term economic development through tourism, recreation, and sustainable fisheries—industries that already account for a large portion of the region’s economy.

Conversely, the timber industry and some local leaders argue that selective logging, especially second-growth harvesting, can be conducted responsibly and provide vital jobs in isolated communities.

What’s clear is that the decisions made about the Tongass today will have global implications for biodiversity, climate stability, and the future of public lands in the United States.

Birding, Boating, and Sustainable Tourism

While the timber debate simmers, a quieter revolution is unfolding in the forest’s tourism economy. Increasingly, visitors are coming not to harvest trees—but to experience the majesty of the Tongass firsthand.

Birding tours, kayaking trips through Misty Fjords, wildlife photography excursions, and Indigenous-led cultural experiences are just a few of the ways travelers can immerse themselves in this rich environment. The Southeast Alaska Birding Trail, for example, is a prime model of how conservation and economic development can work together. Designed to attract birders and ecotourists, it helps channel revenue into communities while educating visitors about the importance of the surrounding ecosystems.

The trail’s mobile app enhances accessibility even further by allowing travelers to explore without internet connection—an essential feature in such a remote area. This kind of low-impact tourism is viewed by many as a viable alternative to logging, helping communities transition toward economies that prioritize preservation over extraction.

Why Tongass Matters Now More Than Ever

At a time when forests are vanishing worldwide, the Tongass offers a rare glimpse of what remains—and a chance to protect it before it’s too late.

Here lies a forest that supports salmon runs critical to global food supplies, habitats for threatened bird species, and cultural legacies spanning millennia. It’s a place where climate solutions take root in mossy soil and snow-fed rivers, where bears and eagles still roam free under canopies that have stood for hundreds of years.

But all of this depends on what we choose to do next.

Quick Facts About Tongass National Forest

-

Location: Southeastern Alaska, US

-

Size: ~17 million acres (26,560 square miles)

-

Established: 1907 (by executive order); 1909 (formal legislation)

-

Indigenous Peoples: Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian

-

Ecosystems: Temperate rainforest, alpine tundra, muskeg, tidewater glaciers

-

Wildlife: Brown and black bears, Sitka black-tailed deer, wolves, eagles, salmon, marbled murrelets

-

Key Attractions: Misty Fjords National Monument, Admiralty Island, Southeast Alaska Birding Trail

-

Conservation Status: One-third wilderness, one-fifth commercial use, remaining areas under debate

FAQs About Tongass National Forest

Can you visit Tongass National Forest?

Yes! There are numerous ways to explore the Tongass, from guided wildlife tours and cruises to self-guided hiking, kayaking, and birding. Access points include Juneau, Ketchikan, Sitka, and other southeastern Alaska communities.

What makes the Tongass so important for climate change?

The Tongass stores more carbon than any other type of forest on Earth, making it a vital natural resource for carbon sequestration and climate resilience.

Are parts of the Tongass protected?

Yes. Roughly one-third of the forest is designated as wilderness, which prohibits logging and road construction. However, other parts remain open to timber harvest and development, depending on federal policy.

What wildlife can I expect to see in the Tongass?

Depending on where and when you visit, you might see brown bears, black bears, wolves, bald eagles, salmon, otters, and a wide range of bird species—including rare ones like the marbled murrelet.

How can I explore the birding trail?

Download the Southeast Alaska Birding Trail app on Apple or Android. The app provides maps, directions, and species checklists—even without internet access.

The Heartbeat of Alaska’s Wilderness

Tongass National Forest is more than just America’s largest forest—it’s a living mosaic of ecosystems, traditions, and opportunities. It’s where salmon spawn and eagles soar, where Indigenous stories are etched into cedar canoes, and where the future of conservation is still being written. For those who care about wild places, biodiversity, and climate resilience, the Tongass isn’t just worth a visit—it’s worth protecting.