Gates of The Arctic National Park

Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve is one of the most extraordinary and untouched landscapes in the United States. Located entirely north of the Arctic Circle in northern Alaska, this vast wilderness protects a significant portion of the central Brooks Range. Covering over 8.5 million acres, it is the second-largest national park in the country, behind only Wrangell–St. Elias National Park. Despite its immense size, Gates of the Arctic is the least visited national park in the United States, welcoming only 7,362 recreational visitors in 2021.

This remote, roadless, and trail-free expanse preserves Alaska’s wild heart in its rawest form. It is a land where permafrost shapes the ground, caribou migrate by the hundreds of thousands, and no visitor center interrupts the horizon. Here, the silence is broken only by the wind across alpine ridges or the flow of a river cutting through glacier-carved valleys. For those seeking true solitude and untouched natural beauty, Gates of the Arctic offers a rare and awe-inspiring opportunity.

A Protected Wilderness of Historic Proportions

Originally designated as a national monument on December 1, 1978, Gates of the Arctic became a national park and preserve through the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) in 1980. Today, about 85 percent of the park is further protected as wilderness, covering over 7.1 million acres. It borders the Noatak Wilderness, and together they create the largest contiguous wilderness area in the United States.

The park was established to preserve the undeveloped and pristine character of Alaska's central Brooks Range. It also provides opportunities for wilderness recreation and supports traditional subsistence uses by local Indigenous communities.

Geography: Mountain Peaks, Arctic Rivers, and Untouched Valleys

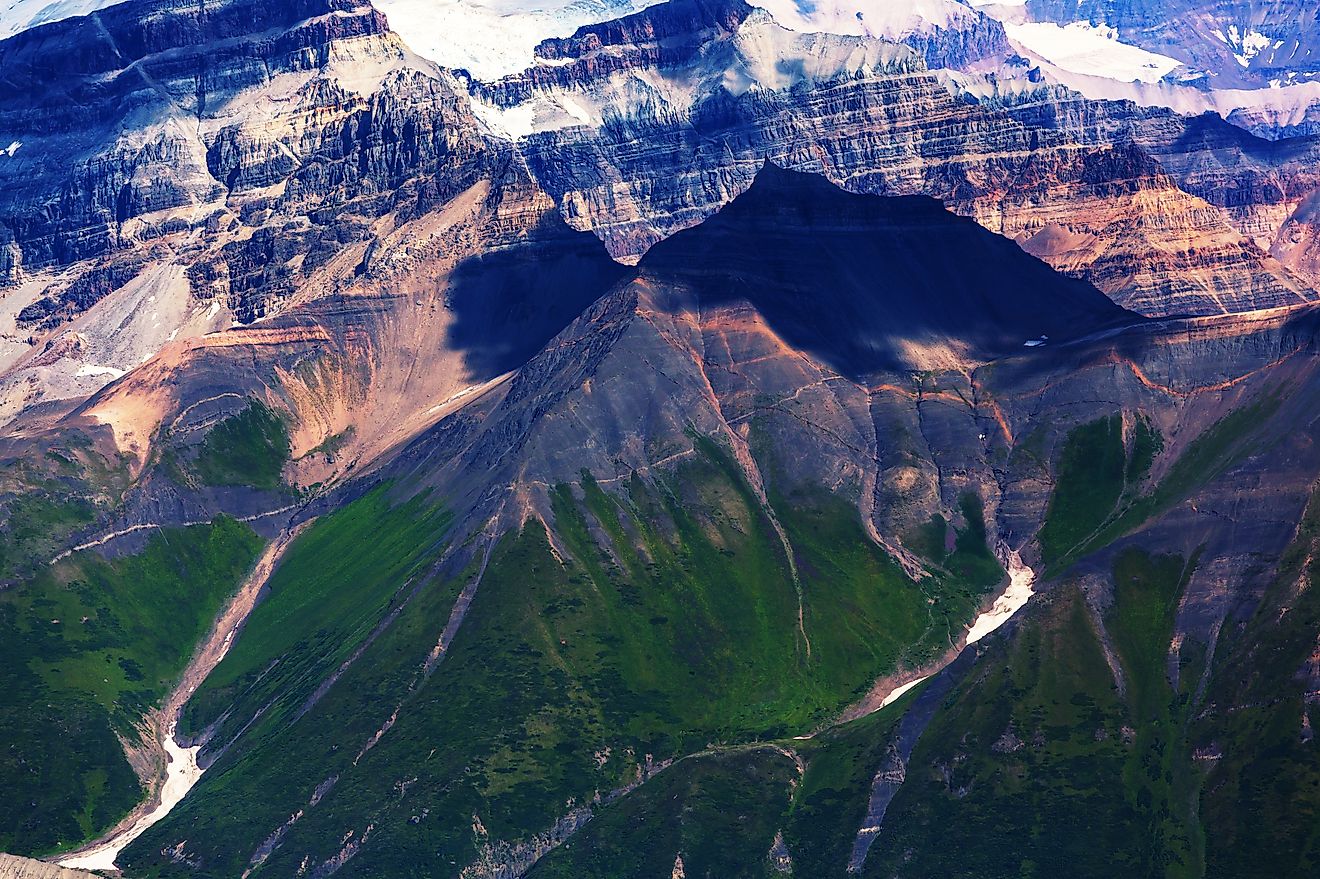

The geography of Gates of the Arctic is defined by rugged terrain and dramatic contrasts. The park spans both the north and south slopes of the Brooks Range and includes prominent mountain groups such as the Endicott Mountains and Schwatka Mountains. The Continental Divide runs through the park, separating waters that flow into the Arctic Ocean from those that head southward.

To the south lie the Kobuk-Selawik Lowlands, which cradle the headwaters of the Kobuk River. Between the mountains, glacial valleys are scattered with alpine lakes, creating a landscape that feels truly prehistoric. The park also includes unique detached units around Fortress Mountain and Castle Mountain.

Ten small communities near the park, including Anaktuvuk Pass, Wiseman, and Bettles, are recognized as “resident zone communities” due to their reliance on park resources for food and cultural survival.

No Roads, No Trails, No Campgrounds

Gates of the Arctic has no roads, trails, or established visitor facilities within its boundaries. Access requires significant planning and often involves flying into the park via small bush planes. The Dalton Highway, located about five miles from the park's eastern boundary, offers the closest road access, although reaching the park from there still requires crossing rivers and rough terrain.

Camping is allowed throughout the park, although easement restrictions may apply when crossing Native Corporation lands. Sport hunting is permitted in the preserve section of the park, but not in the national park portion, where only subsistence hunting by local rural residents is allowed.

The park’s headquarters are located in Fairbanks. Ranger operations within the park are managed from the Bettles Ranger Station. Additional visitor information is available at the Arctic Interagency Visitor Center in Coldfoot, open seasonally from late May through early September.

Climate: Harsh, Extreme, and Rapidly Changing

The climate in Gates of the Arctic is classified as subarctic, featuring cool summers and extremely cold winters. At Anaktuvuk Pass, the average annual extreme minimum temperature is about −42 degrees Fahrenheit. Winter temperatures can plunge as low as −75 degrees, while summer highs may briefly reach 90 degrees.

The park’s climate is changing rapidly. From 1985 to 2017, the area of perennial snowfields shrank by nearly 13 square kilometres. Thawing permafrost is destabilizing soil structures, increasing erosion, and altering the landscape. These changes threaten both ecosystems and the traditional ways of life for Indigenous communities.

Ecology: A Harsh Home for Resilient Life

Despite its harsh conditions, Gates of the Arctic is rich in biodiversity. South of the Brooks Range lies the boreal forest, populated by black and white spruce along with poplar. North of the range, vegetation thins out into tundra and Arctic desert.

The park supports a wide array of wildlife. Mammals include brown bears, black bears, moose, Dall sheep, muskoxen, wolverines, wolves, coyotes, lynxes, porcupines, and Arctic foxes. The rivers contain grayling, Arctic char, and chum salmon, providing essential food for both people and animals.

Birds of prey such as golden eagles, bald eagles, peregrine falcons, and ospreys dominate the skies, while owls and terns thrive across the varied terrain.

One of the park’s most spectacular phenomena is the mass migration of caribou. More than half a million animals from the Central Arctic, Western Arctic, Teshekpuk, and Porcupine herds traverse the Brooks Range every year. This migration plays a crucial role in the subsistence lifestyle of Indigenous groups and is a key ecological process in the region.

Wild and Scenic Rivers

Six designated Wild and Scenic Rivers run through Gates of the Arctic. These rivers provide outstanding opportunities for remote paddling adventures and wildlife viewing. The rivers are:

-

Alatna River (83 miles)

-

John River (52 miles)

-

Kobuk River (110 miles)

-

North Fork of the Koyukuk River (102 miles)

-

Tinayguk River (44 miles)

-

Portion of the Noatak River

Each river winds through alpine valleys and dramatic canyons, offering an unfiltered view of Alaska’s interior wilderness.

Human History: 12,000 Years of Survival

The human history of the Brooks Range stretches back at least 12,500 years. Early nomadic cultures relied heavily on caribou and other wildlife. Artifacts found at sites like Iteriak Creek and Itkillik Lake reveal projectile points, stone tools, and evidence of complex subsistence lifestyles.

The Inupiat people arrived around 1200 AD and became known as the Nunamiut. These inland hunters remained largely isolated until the early 20th century, when declining caribou populations forced many to leave. A resurgence in caribou numbers in the 1930s led to their return and the founding of Anaktuvuk Pass, which remains one of the few permanent settlements in the region.

The Gwich'in people, part of the Northern Athabaskan cultural group, also inhabited the area, particularly south of the Brooks Range.

The Birth of a National Park

The modern effort to protect the Brooks Range gained momentum in the early 20th century. In 1929, explorer and conservationist Bob Marshall traveled along the North Fork of the Koyukuk River and passed between two striking peaks: Frigid Crags and Boreal Mountain. He named this dramatic portal “The Gates of the Arctic.”

Marshall’s writing and advocacy inspired a generation of conservationists. In the 1940s, naturalist Olaus Murie began promoting the idea of permanent protection for Alaskan wildlands.

During the 1960s, proposals emerged to create a national park in the region. By 1968, a National Park Service team recommended preserving more than 4 million acres. Political disagreements delayed legislation, so President Jimmy Carter used the Antiquities Act in 1978 to create Gates of the Arctic National Monument. Congress passed ANILCA two years later, officially establishing Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve.

A Place for the Few Who Dare

Visiting Gates of the Arctic is not for the casual tourist. With no roads, facilities, or services, entering the park requires self-sufficiency, advanced wilderness skills, and a deep respect for nature’s unpredictability. Most travelers access the park via air taxis from Bettles, Coldfoot, or other nearby communities. Once inside, there are no signs, no rangers, and no rescue teams on standby.

Despite these challenges, those who venture into this untouched wilderness often describe the experience as life-changing. It is one of the last true frontiers, where the land shapes your every decision and where nature remains completely in charge.