Glen Canyon Dam

Rising from the red rock canyons of northern Arizona near the town of Page, the Glen Canyon Dam stands as one of the most iconic and contentious engineering marvels in the American West. Spanning the Colorado River, this massive concrete arch-gravity dam not only created Lake Powell—one of the largest artificial reservoirs in the United States—but also became a pivotal piece of the Southwest’s water infrastructure.

Today, it remains a critical hydroelectric power source and a lightning rod in environmental debates, emblematic of the region’s fragile balance between development and conservation.

Building the Dam: Engineering in the Desert

Constructed between 1956 and 1966 by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the Glen Canyon Dam was envisioned as a cornerstone of the Colorado River Storage Project—a broader federal effort to provide consistent water supplies to the Upper Basin states of Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico. At 710 feet high and 1,580 feet long, the dam is a concrete behemoth nestled between steep canyon walls.

The construction effort was monumental. More than 5.4 million cubic yards of concrete and 28.6 million pounds of reinforcing steel went into its creation. Positioned about 16.5 miles upstream of Lee’s Ferry, the dam was sited where the bedrock was stronger and construction materials—like gravel—were more accessible. Before the main dam could even be built, two massive diversion tunnels were blasted through the canyon walls in 1956 to reroute the Colorado River’s flow.

Concrete pouring began in earnest in 1959, and for four years, workers poured an average of 8,000 cubic yards of concrete daily. The construction required an entirely new infrastructure network, including the building of U.S. Route 89 and the Glen Canyon Bridge, a 1,270-foot span that remains one of the tallest bridges in the US today.

Lake Powell: Water Storage and Recreation

When Glen Canyon Dam was closed off in early 1963, the Colorado River began to back up into the red rock canyons of Glen Canyon, eventually forming Lake Powell. It took 17 years for the reservoir to completely fill, finally reaching its maximum elevation of about 3,610 feet in 1980.

Lake Powell, with a storage capacity of approximately 26.7 million acre-feet, is now the second-largest man-made reservoir in the United States, surpassed only by Lake Mead in Nevada. It plays a crucial role as a water storage basin for the Upper Basin states, helping them fulfill water delivery obligations to the Lower Basin states and Mexico under the 1922 Colorado River Compact and the 1944 Mexican Water Treaty.

Beyond its vital water management purpose, Lake Powell has become a hub for outdoor recreation. Its roughly 2,000 miles of sinuous shoreline, punctuated by hidden coves and towering cliffs, draws millions of visitors each year. Boating, fishing, kayaking, and camping are especially popular in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area that surrounds the lake.

Powering the Southwest: Hydroelectric Benefits

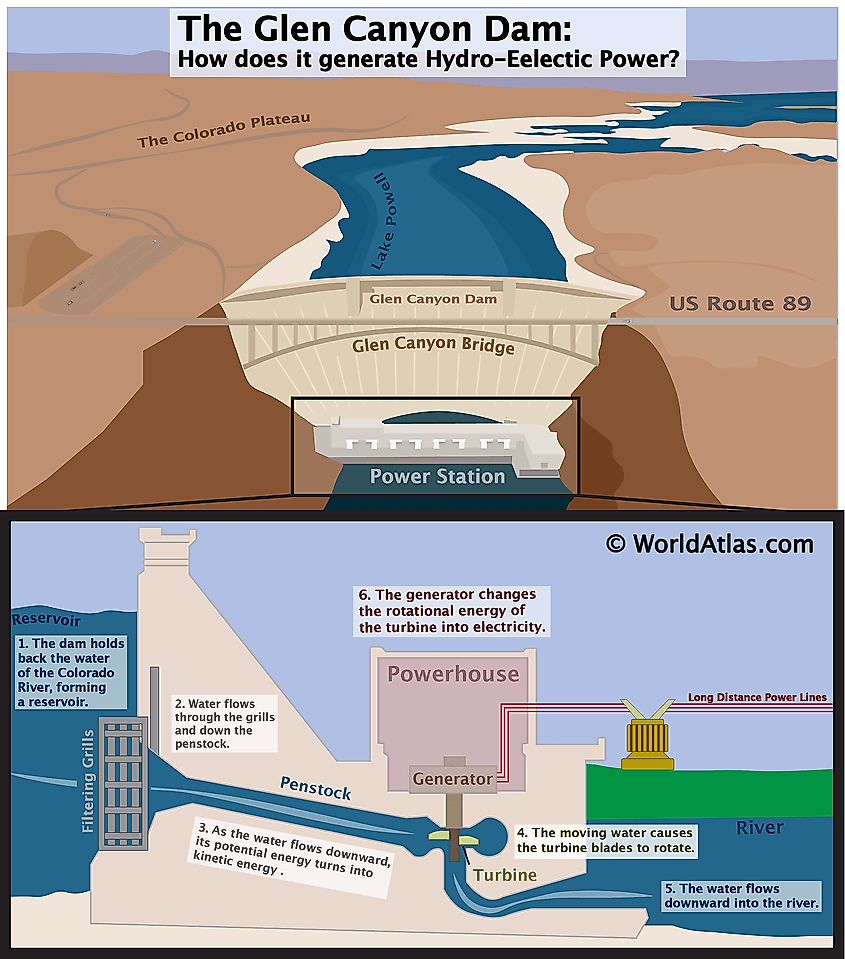

In addition to managing water resources, Glen Canyon Dam plays a significant role in energy production. After the dam wall was completed in 1963, construction of the power plant and spillways began. On September 4, 1964, the dam generated its first electricity.

Today, Glen Canyon’s hydroelectric power plant is the second-largest in the American Southwest. It houses eight generators capable of producing more than 4 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually. The electricity serves about 5 million customers across seven states, offering a relatively clean and renewable energy source in a region heavily reliant on power.

Environmental Costs and Ongoing Challenges

Despite its engineering triumphs, Glen Canyon Dam has become a focal point in the ongoing debate over the environmental cost of large dams. The closure of Glen Canyon dramatically altered the natural flow and ecology of the Colorado River. One of the most profound impacts has been the reduction in sediment and nutrients downstream, disrupting habitats and spawning grounds for aquatic species.

Native fish species, including the bonytail chub, roundtail chub, and Colorado squawfish, have suffered significantly. Three are now extinct, while five others are listed as endangered. The colder, clearer, and sediment-free water released from the dam has proven inhospitable to species that evolved in a dynamic and silty river environment.

Invasive species have also flourished. Non-native fish like smallmouth bass, striped bass, and channel catfish now thrive in Lake Powell and have spread into the river system, outcompeting or preying on native species. Additionally, mollusks like zebra and Quagga mussels pose a significant threat to infrastructure and biodiversity.

The lake itself faces an uncertain future. Ongoing droughts, exacerbated by climate change, have led to critically low water levels in Lake Powell. At times, the reservoir has dropped so low that officials have warned of a “dead pool” scenario, where water can no longer pass through the turbines to generate electricity. Reduced snowpack in the Rockies and overuse across the basin threaten the long-term viability of both the dam and the reservoir it created.