US Cities That Have No Grid System

Many American cities are known for their orderly, checkerboard-style grid layouts. New York, Chicago, and Phoenix are prime examples of how this pattern helps drivers and pedestrians move through a city with predictable ease. Yet, not every city followed this plan. Across the United States, there are notable urban centers where the grid system never took hold, leaving streets to twist, curve, and intersect in ways that often defy logic but add immense character.

From historical origins to geographic constraints, the reasons for these non-grid patterns vary, and they have shaped the culture, navigation, and identity of each place. Below, we look at some of the most famous American cities where straight lines give way to winding routes and angled avenues.

Boston, Massachusetts

-

Population: Approximately 650,000

-

Founding Year: 1630

-

Street Style: Organic, colonial-era roads shaped by early settlement

Boston is perhaps the most famous example of a major American city that lacks a traditional grid system. Its streets twist, turn, and often seem to lead nowhere in particular. This can make driving a challenge, but it also gives Boston its charm.

The city’s origins date back to the early 1600s, long before the idea of systematic grids took hold in America. Settlers built roads along natural paths, connecting homes, markets, and the harbor. As Boston expanded, these routes became permanent streets. The result is a web of narrow lanes and irregular intersections, especially in older neighborhoods such as the North End and Beacon Hill.

Today, Boston’s street layout contributes to its historic feel. Tourists often find the unpredictability part of the experience, whether wandering along the Freedom Trail or navigating around Boston Common. Public transportation and pedestrian-friendly areas make it easier to handle the lack of a grid, but drivers may need patience and a reliable GPS.

San Francisco, California

-

Population: Approximately 810,000

-

Founding Year: 1776

-

Street Style: Partial grid disrupted by hills and topography

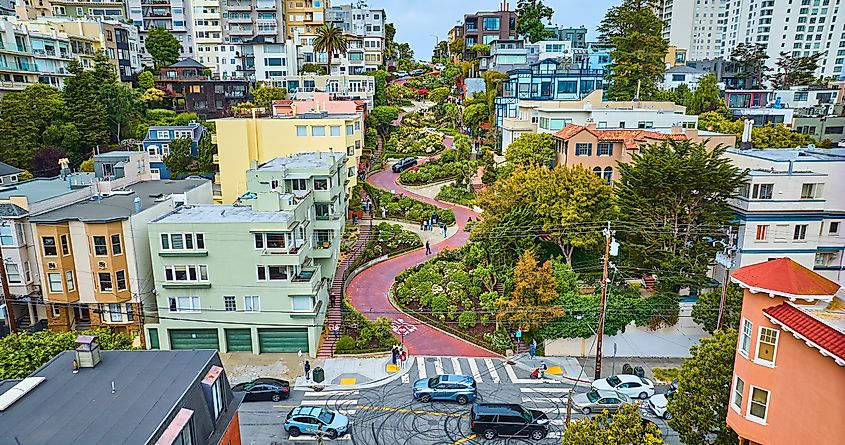

At first glance, San Francisco appears to have a grid in some areas, but its layout is far from consistent. The city’s famous hills have played a major role in breaking the grid and forcing streets to adapt to the landscape.

San Francisco’s original planners did attempt a grid, but they underestimated the city’s steep terrain. Streets that would have formed neat right angles on flat land instead rise at extreme angles or stop abruptly where hills became impassable. In places like Russian Hill and Telegraph Hill, roads twist and curve to accommodate the slopes.

Perhaps the most iconic example is Lombard Street, known as the “crookedest street in the world.” Its series of tight hairpin turns illustrates how the city adapted its layout to steep terrain rather than forcing a rigid grid.

New Orleans, Louisiana

-

Population: Approximately 375,000

-

Founding Year: 1718

-

Street Style: Mixed, with curved roads shaped by the river's bend

New Orleans has a distinctive layout that resists the typical grid, especially in its historic French Quarter. Instead, streets follow the curves of the Mississippi River, giving the city a crescent-like shape in certain areas.

Founded by the French in 1718, New Orleans was designed with the river as its focal point. Early streets were aligned to the Mississippi’s curve, creating irregular angles that remain to this day. As the city expanded outward, newer areas adopted more conventional planning, but the historic core retains its unique configuration.

Visitors often find that cardinal directions mean little in New Orleans. Locals give directions based on the river or the lake (Lake Pontchartrain), using terms like “upriver” and “downriver” instead of north or south. This system reflects the city’s intimate connection to its waterways.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

-

Population: Approximately 300,000

-

Founding Year: 1758

-

Street Style: Triangular layout shaped by river confluence

Pittsburgh is another city where geography overruled any attempt at a neat grid. Situated at the confluence of three rivers and surrounded by steep hills, the city’s streets curve, split, and rejoin in ways that baffle newcomers.

Pittsburgh’s layout developed to accommodate its rivers: the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio. Bridges, tunnels, and inclines shape the flow of traffic, often creating sharp turns or abrupt changes in direction. Some streets follow old Native American trails or early settlement paths that predate modern planning.

For those accustomed to a grid, driving in Pittsburgh can be an adventure. GPS is often a necessity, especially when navigating neighborhoods like Mount Washington or the South Side. However, the city’s unique layout also offers stunning views and a strong sense of character.

Seattle, Washington

-

Population: 733,919

-

Founded: 1851

-

Street Layout Style: Multiple grids, angled and irregular

Seattle presents a particularly interesting case because it has overlapping grids that do not align with one another. This leads to streets meeting at odd angles, creating triangular blocks and unexpected intersections.

Downtown Seattle was originally laid out by two groups of settlers with different visions. One grid followed the shoreline of Elliott Bay, while another aligned with the cardinal directions. When these two systems met, they did not match, and the resulting compromise created a patchwork pattern that persists today.

For pedestrians, the irregular layout creates unique spaces such as the famous Pioneer Square. For drivers, it can be confusing, with streets like Yesler Way cutting diagonally across otherwise orderly blocks.

Why These Cities Rejected the Grid

These cities did not necessarily reject the grid by choice; instead, their unique landscapes, historical timelines, and development needs often dictated a more organic layout. In many cases, rugged terrain, winding rivers, and natural barriers made straight, evenly spaced streets nearly impossible to implement without significant alteration to the land. Cities that emerged before the grid became a common planning tool frequently grew around harbors, hills, and trading hubs, prioritizing access and commerce over uniformity.

As these cities expanded, they often retained their original, irregular routes, weaving them into newer districts rather than erasing their past. This blend of practicality and history explains why their streets still twist, curve, and intersect at odd angles today, offering a glimpse into the priorities and challenges of their early settlers.

Impact on Daily Life and Tourism

Living in or visiting a city without a grid system can be both frustrating and delightful. The winding, unpredictable streets may confuse drivers and pedestrians at first, but they also encourage slower exploration and a sense of discovery. Instead of uniform blocks and predictable intersections, these cities often reveal unexpected turns that lead to historic landmarks, hidden courtyards, or quiet plazas that feel tucked away from the main flow of traffic.

This lack of rigid order allows neighborhoods to develop their own rhythm and personality, with streets that follow the land’s natural contours or preserve centuries-old pathways. For many visitors, this creates a sense of adventure where each walk or drive feels less like following a map and more like unfolding a story around every corner.

Final Thoughts

The lack of a grid system in cities like Boston, San Francisco, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, and Seattle is not a flaw but a feature. These places remind us that urban life is not always about straight lines and right angles. Their winding streets tell stories of early settlers, natural obstacles, and evolving priorities. While a grid might make for easier navigation, it rarely creates the same sense of intrigue.

So next time you find yourself circling a block in Boston or puzzling over a fork in Pittsburgh, remember that you are experiencing a piece of history. Non-grid cities are a living testament to how humans adapt their environments to fit the land, rather than the other way around.