How Did Hawaii Become Part of The United States?

Today, Hawaii is celebrated for its natural beauty, unique culture, and strategic location in the Pacific Ocean. But its journey to becoming the 50th US state is one marked by political intrigue, economic interests, and cultural upheaval. The path from an independent kingdom to American statehood was neither quick nor straightforward.

To understand how Hawaii became part of the United States, we need to examine the kingdom’s rich history, the influence of American business interests, and the contentious overthrow that changed the course of its future.

The Hawaiian Kingdom: A Sovereign Nation

Before Hawaii was a US state—or even a territory—it was a sovereign and internationally recognized kingdom. The unification of the Hawaiian Islands was achieved by King Kamehameha I in 1810 after years of conflict among warring island chiefs. Under his rule, Hawaii began trading with Western powers and adopting aspects of European-style governance.

By the mid-1800s, Hawaii had a functioning constitutional monarchy, a written legal code, and diplomatic relations with major world powers, including the United States, Great Britain, and France. In 1843, Britain officially recognized Hawaiian independence, and in 1849, the United States signed a formal treaty of friendship and commerce with the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Economic Ties with the United States

Hawaii's economy during the 19th century became increasingly tied to the United States, particularly through the sugar industry. American missionaries had first arrived in the 1820s, followed by waves of American businessmen who established large-scale sugar plantations. Over time, these entrepreneurs accumulated wealth, land, and political influence.

The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, signed between the US and the Kingdom of Hawaii, allowed Hawaiian sugar to enter the American market duty-free. In exchange, the US gained exclusive use of Pearl Harbor. This agreement strengthened Hawaii’s economic dependence on the United States and deepened American influence in local politics.

By the 1880s, American planters and businessmen had become some of the most powerful figures in Hawaiian society. Many of them, known as the "Big Five" (Castle & Cooke, Alexander & Baldwin, C. Brewer & Co., American Factors, and Theo H. Davies & Co.), would play a central role in shaping Hawaii’s future.

The Overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani

Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last reigning monarch of Hawaii, ascended the throne in 1891 with the intention of restoring power to the monarchy and reducing the influence of foreign interests. In 1893, she attempted to enact a new constitution that would give more power to Native Hawaiians and reduce the dominance of American and European elites.

This move alarmed a group of American businessmen and sugar planters, many of whom were members of the powerful Hawaiian League. With the support of John L. Stevens, the US Minister to Hawaii, these elites organized a coup d’état. On January 17, 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani was overthrown by a group of armed insurgents backed by 162 US Marines from the USS Boston, who were ostensibly sent to protect American lives and property.

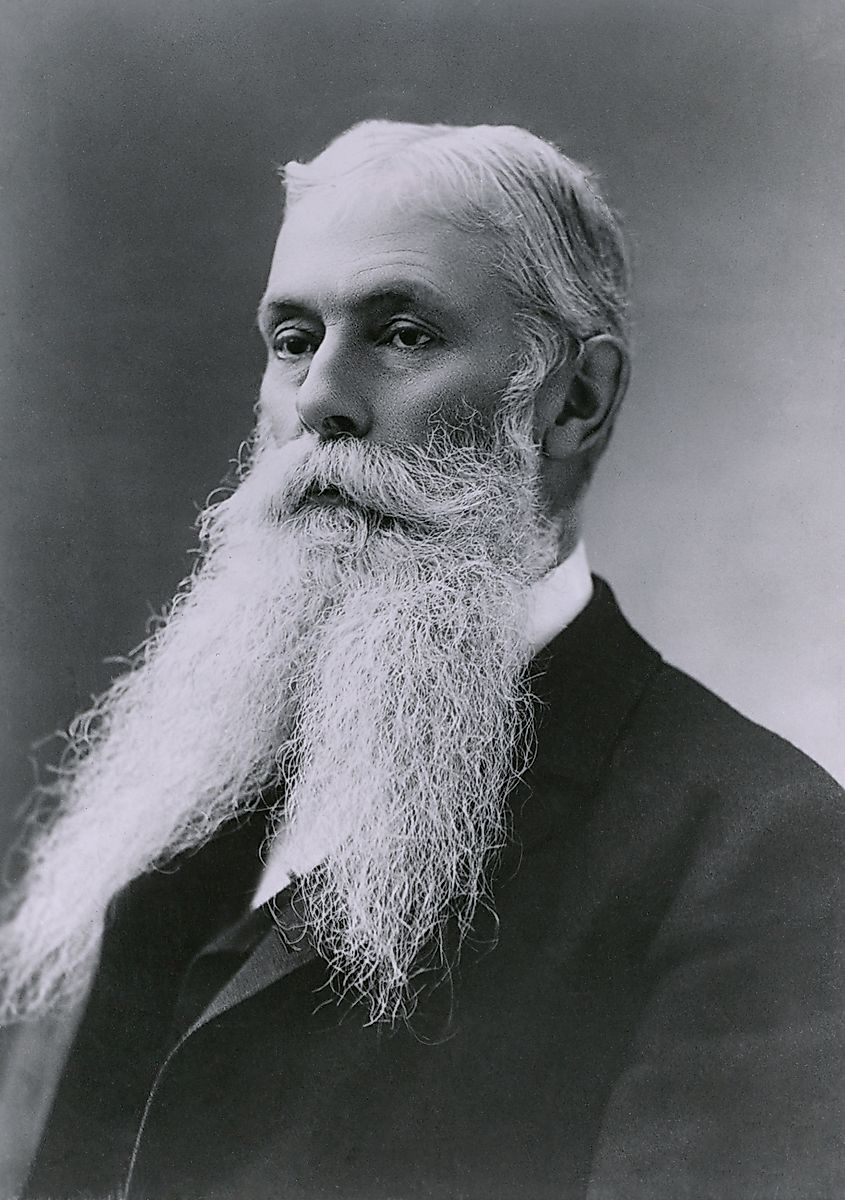

Following the overthrow, the insurgents established a provisional government led by Sanford B. Dole, a prominent American-born lawyer and businessman. Queen Liliʻuokalani surrendered under protest, believing the US government would later rectify the situation.

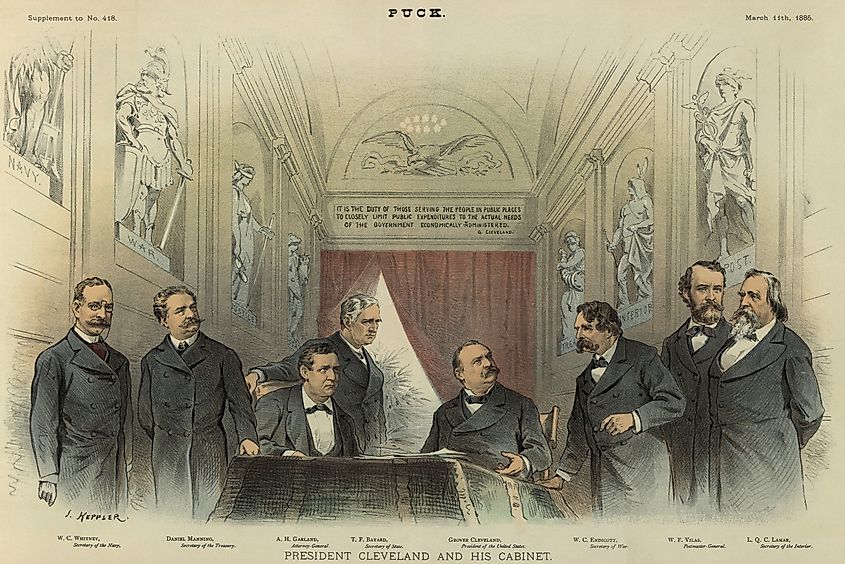

President Cleveland’s Opposition

When news of the overthrow reached Washington, D.C., President Grover Cleveland was alarmed. He opposed the annexation and considered the coup illegal and unjustified. Cleveland sent former Congressman James Blount to investigate the events in Hawaii. The resulting Blount Report concluded that the US had improperly supported the overthrow and that the monarchy should be restored.

Despite Cleveland's efforts, the provisional government refused to relinquish power. Domestic opposition within the US also made reinstating the queen politically difficult. Cleveland eventually referred the matter to Congress, but no decisive action was taken, and the provisional government solidified its control.

The Republic of Hawaii and Push for Annexation

In 1894, the provisional government declared Hawaii a republic, with Sanford Dole as its first president. Despite lacking broad local support, the Republic of Hawaii sought annexation to the United States. At first, annexation efforts stalled due to opposition in both Hawaii and the US.

However, geopolitical factors soon shifted the balance. The outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 dramatically increased Hawaii’s strategic value. The US military saw the islands—particularly Pearl Harbor—as crucial for projecting American power across the Pacific.

That same year, Congress passed the Newlands Resolution, a joint resolution that allowed for the annexation of Hawaii without the need for a formal treaty. On July 7, 1898, President William McKinley signed the resolution, and Hawaii officially became a US territory on August 12, 1898.

Hawaii as a US Territory

As a US territory, Hawaii’s government remained under the control of appointed American officials, and Native Hawaiians lost much of their political power. The Territorial Government Act of 1900 granted US citizenship to Hawaiian residents but denied them the right to vote for president or have voting representation in Congress.

During this period, Hawaii’s economy continued to grow, dominated by sugar and pineapple industries. Immigrants from China, Japan, the Philippines, Portugal, and Korea arrived in large numbers to work on plantations, further transforming the cultural and demographic landscape of the islands.

Pearl Harbor’s importance increased, especially after the 1941 Japanese attack that brought the US into World War II. The attack not only devastated the naval base but also placed Hawaii at the center of America's Pacific military strategy.

The Road to Statehood

Following World War II, calls for Hawaiian statehood gained momentum. Hawaii’s population had become more diverse and more politically active. Native Hawaiians and other local groups advocated for full rights and representation in the federal government.

One major barrier to statehood had been racial prejudice. Some US lawmakers were reluctant to admit a state with a majority non-white population. However, the post-war civil rights movement and Hawaii’s demonstration of loyalty during WWII helped change public opinion.

In 1959, Congress passed the Hawaii Admission Act, and on August 21, 1959, Hawaii officially became the 50th state of the United States following a public referendum in which over 90% of voters supported statehood.

Controversy and Cultural Impact

The annexation and subsequent statehood of Hawaii remain deeply controversial, particularly among Native Hawaiians. Many believe that the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani was an illegal act of imperialism and that the US government never had the right to take over the islands.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution, formally acknowledging and apologizing for the US role in the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. The resolution stated that the Native Hawaiian people never relinquished their sovereignty and that the US acted improperly.

Today, movements for Hawaiian sovereignty and self-determination continue, with some advocating for federal recognition of Native Hawaiians similar to that of Native American tribes, while others push for full independence.

Final Thoughts: A Complex Legacy

The story of how Hawaii became part of the United States is a multifaceted tale of power, politics, and identity. What began as a thriving Polynesian kingdom was transformed through missionary influence, economic exploitation, and strategic necessity into a US state.

While many Americans view Hawaii as a paradise vacation spot or a proud addition to the United States, the deeper history tells a more complex story—one that involves loss of sovereignty, cultural resilience, and ongoing debates about justice and autonomy. Understanding this history is essential to appreciating the full richness of Hawaii’s past and present.